Recreated by Anthony Hutchings. Around what is now the ‘Bexhill area’ 135 million years ago: a spinosaur (centre) seizes the carcass of an ornithopod, much to the annoyance of a smaller tyrannosaur (left) and dromaeosaurids (right).

Research led by the University of Southampton has revealed that several groups of meat-eating dinosaur stalked the Bexhill area 135 million years ago. The study, published this week in Papers in Palaeontology, has discovered a whole community of predators belonging to different dinosaur groups – including Tyrannosaurs, Spinosaurs and members of the Velociraptor family.

It’s the first time tyrannosaurs have been identified in sediments of this age and region.

“Meat-eating dinosaurs – properly called theropods – are rare in the Cretaceous sediments of southern England,” said Dr Chris Barker, visiting researcher at the University of Southampton and lead author of the research. “Usually, Isle of Wight dinosaurs attract most of our attention. Much less is known about the older Cretaceous specimens recovered from sites on the mainland.”

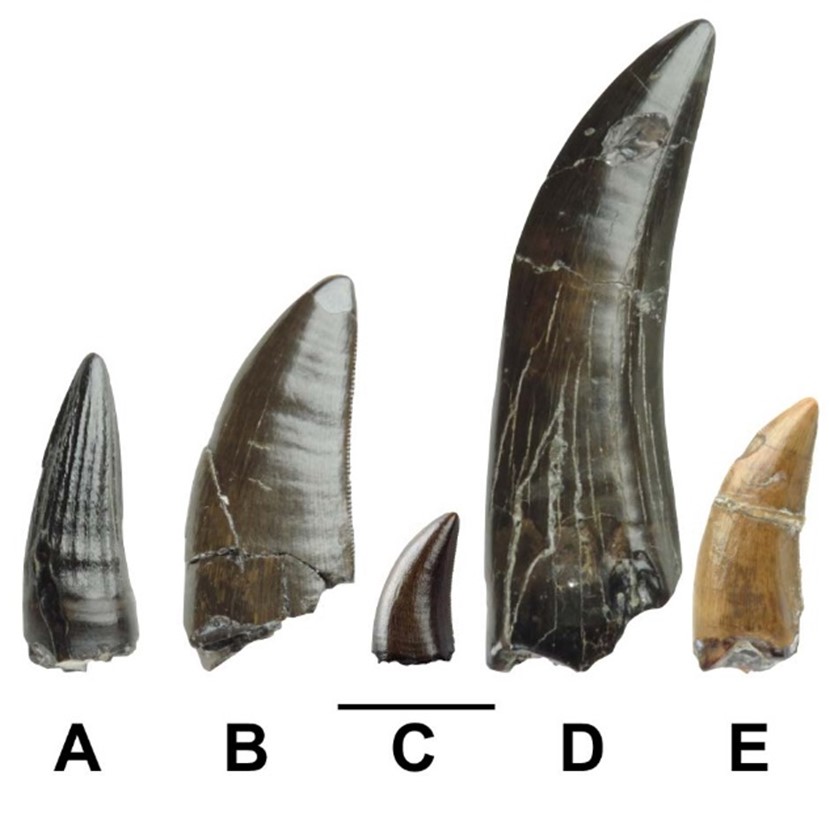

The new Bexhill dinosaurs are represented by teeth alone. Some of the fossilised teeth are on display at Bexhill Museum.

Theropod teeth are complex, and vary in size, shape, and in the anatomy of their serrated edges. The University of Southampton team used several techniques to analyse the fossils, including phylogenetic, discriminant and machine learning methods, teaming up with colleagues at London’s Natural History Museum, the Hastings Museum and Art Gallery, and the Museo Miguel Lillo De Ciencias Naturales in Argentina.

“Dinosaur teeth are tough fossils and are usually preserved more frequently than bone. For that reason, they’re often crucial when we want to reconstruct the diversity of an ecosystem”, says Dr Barker.

“Rigorous methods exist that can help identify teeth with high accuracy. Our results suggest the presence of spinosaurs, mid-sized tyrannosaurs and tiny dromaeosaurs – Velociraptor-like theropods – in these deposits”.

The discovery of tyrannosaurs is particularly notable, since the group hasn’t previously been identified in sediments of this age and region. These tyrannosaurs would have been around a third of the size of their famous cousin Tyrannosaurus rex, and likely hunted small dinosaurs and other reptiles in their floodplain habitat.

“Assigning isolated teeth to theropod groups can be challenging, especially as many features evolve independently amongst different lineages. This is why we employed various methods to help refine our findings, leading to more confident classifications,” says Lucy Handford, co-author of the paper and former University of Southampton Master’s student, who is now undertaking a PhD at the University of York.

“It’s highly likely that reassessment of theropod teeth in museum stores elsewhere will bring up additional discoveries.”

Discovery at Ashdown Brickworks

The tireless collecting of retired quarryman Dave Brockhurst, who has spent the last 30 years uncovering the fossils from Ashdown Brickworks, was key to the discovery.

Dave has uncovered thousands of specimens, ranging from partial dinosaur skeletons to tiny shark teeth. Around 5000 of his discoveries have already been donated to Bexhill Museum. Theropods are exceptionally rare at the site, and Dave has only found ten or so specimens there so far.

“As a child I was fascinated by dinosaurs and never thought how close they could be,” says Mr Brockhurst. “Many years later I started work at Ashdown and began looking for fossils. I’m happy with tiny fish scales or huge thigh bones, although the preservation of the dinosaur teeth really stands out for me.”

Exciting find

Dr Darren Naish, a co-author of the study, added: “Southern England has an exceptionally good record of Cretaceous dinosaurs, and various sediment layers here are globally unique in terms of geological age and the fossils they contain.

“These East Sussex dinosaurs are older than those from the better-known Cretaceous sediments of the Isle of Wight, and are mysterious and poorly known by comparison. We’ve hoped for decades to find out which theropod groups lived here, so the conclusions of our new study are really exciting.”

Dr Neil Gostling, also from the University of Southampton, supervised the project. He said: “This project shows that museum collections, curators, and collectors are vital for pushing forward our understanding of the diversity of dinosaurs, and other extinct groups. We’re also very thankful to Ashdown Brickworks for their cooperation in preserving the quarry’s important palaeontological heritage.

“200 years after the naming of the first dinosaur, Megalosaurus, there are still really big discoveries to be made. Dinosaur palaeobiology is alive and well.” Several of the specimens are on display at Bexhill Museum.

The research was funded by the University of Southampton’s Institute for Life Sciences. Theropod dinosaur diversity of the lower English Wealden: analysis of a tooth-based fauna from the Wadhurst Clay Formation (Lower Cretaceous: Valanginian) via phylogenetic, discriminant and machine learning methods is published by Papers in Palaeontology and is available online.