Bitter years passed between Britain’s abolition of the slave trade in February 1807 and the abolition of slavery itself in July 1833. An estimated 410,000 slaves had been taken through the Caribbean by British slave traders in the years before. Most were bound for the United States, but a third were set to work on British owned plantations in the West Indies.

A folder of legal documents in Bexhill Museum’s archives gives a clue to the fate of some of these enslaved men, women, and children on the Caribbean island of St Vincent. It also provides a poignant background to the protests demanding reparations for slavery that met The Duke & Duchess of Wessex when they arrived in St Vincent at the weekend.

While the Royal Navy went to war against the slave trade itself, between 1807 and actual abolition, in St Vincent and elsewhere the unravelling of the complex web of contracts and property rights that enabled slavery in British trans-national trade took longer to achieve. Decades later its legacy and effect on the slaves’ descendants is strongly contested.

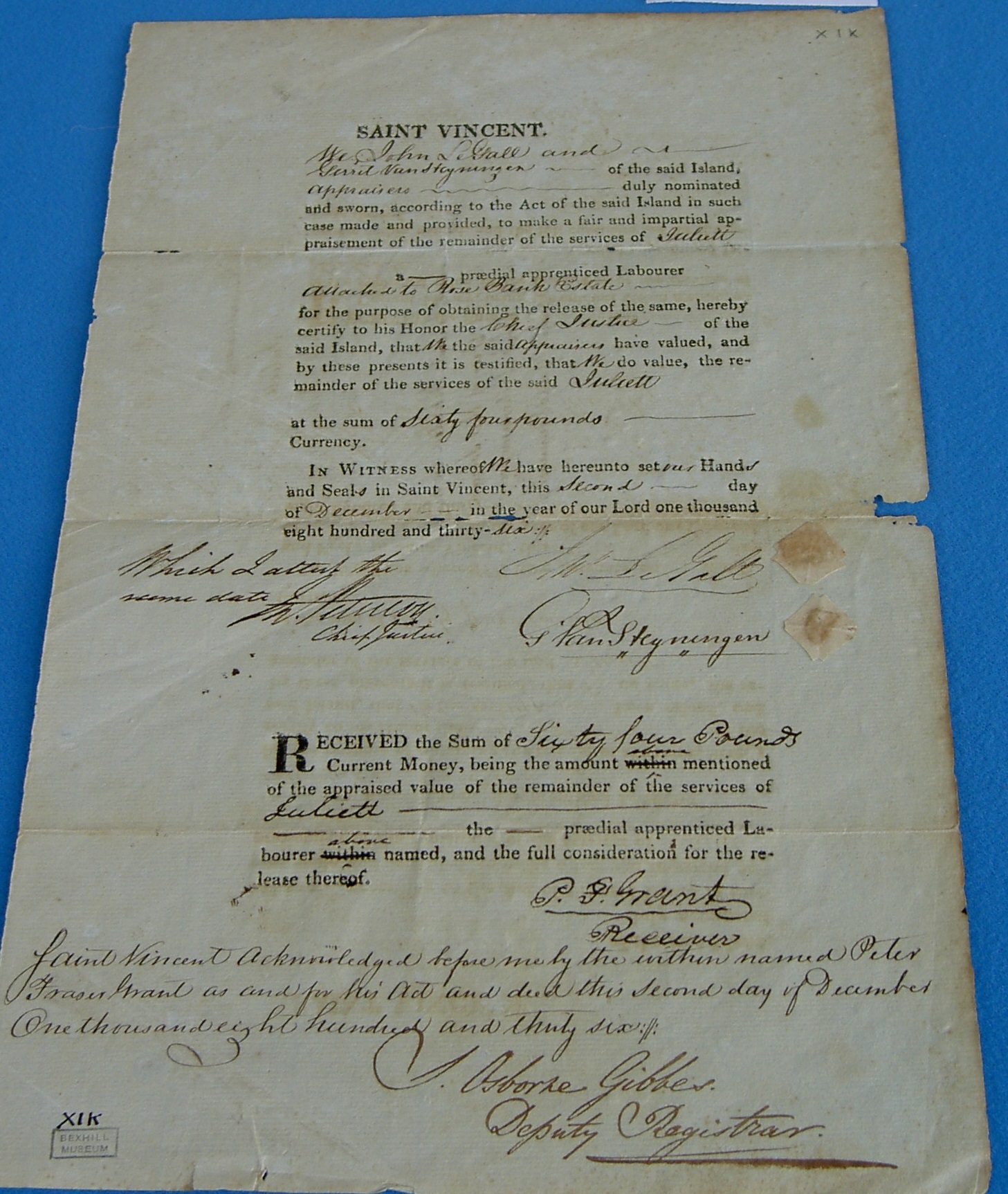

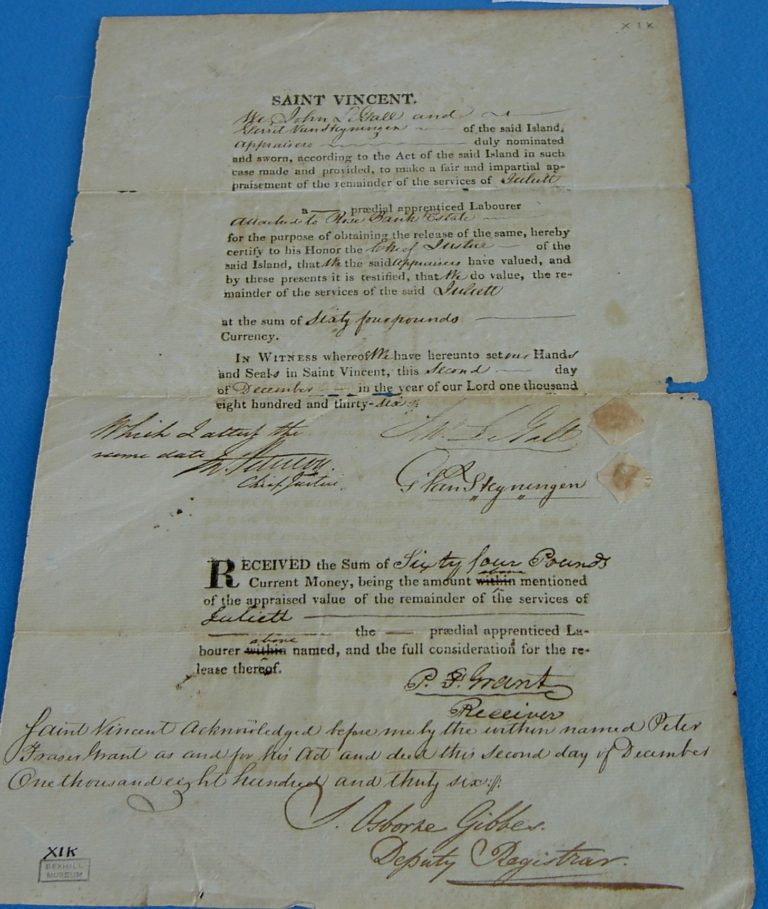

The basic facts are clear though. The Museum’s 20 documents from the period – drafted by European bureaucrats running the islands’ registrar’s office – are some of many providing a forensic analysis of the trading practices of the slavers, and eventually, the nature of ‘Manumission’, the legal means by which slave owners would set slaves free.

Manumission was a separate process under law. It addressed property rights, not human rights, and was pointedly different to government-imposed laws of emancipation, and the abolition of slavery across the British Empire itself. Bluntly, as the museum’s collection of documents reveal, there was too much money involved for it to be made simple.

There are purchases by mortgage, valuation and leasing of slaves, loans with slaves as security, sales of slaves due to the debts of the owner, indentures of apprenticeship and manumission. In some cases, the manumission documents state the compensation given to the slave owner.

It is possible that the papers may have been carefully selected as representative of the type of transactions during the period. How they came to be in the museum is not clear, but most likely they were given in response to a general appeal for historical artefacts when the museum was founded – though it is not recorded who by. (One candidate would be Bexhill vicar Charles Errey, who kept a parish in St Vincent at the turn of the century and wrote a dramatic account of the 1902 eruption of the island’s volcano for the Bexhill Chronicle.)

The handwritten papers were painstakingly deciphered by Bexhill Museum volunteer Mary Hart and put on temporary display at the Museum by curator Julian Porter in 2007, to mark the 200th anniversary of the 1807 act outlawing the British slave trade, if not then the actual practice of slavery.

The St Vincent Papers

Beyond the shocking cruelty of slavery as a practice, a striking aspect of the legal process behind the denial of basic human rights, is its mundane attention to financial details – and in relative terms, the large amounts of money involved.

Document X1g logs the deal struck by slave owner Walter Waters to lease 18 slaves for three years – all named on the paperwork and including two children – to one Charles Warner, setting up a business on a neighbouring island. Warner was charged a yearly fee of £124 12s 10d for the 18, about £21,250 in today’s money. Document X1h details a £1,200 mortgage loan on 6% interest to a Michael & Elizabeth Novacourchy with – as security – 13 slaves, four men, five women, four children, William, Betty, Eleanor, and Sally, plus, not included in the formal total, a baby called Constance. Document X1i unravels a repaid mortgage of £4,913 19s 10d – about £670,000 in today’s money – complicated by a bankruptcy case in Dublin in 1817 and resulting in the ‘return’ of 60 slaves to a partnership of four St Vincent slave owners.

Much is made of the idea that many slave owners kept “good care” of their captives. This had little to do with common humanity. The 18 slaves traded by Waters were ‘valued’ by St Vincent registrar J.Bernard at £1,112 – nearly £160,000 by today’s count. The slave owners were simply protecting their investment by keeping them alive and fit enough to work.

In 1834, Britain outlawed slavery, but also agreed to pay the slave owners compensation equivalent to around 17 billion pounds today – close to 40% of the government’s budget that year. This enormous amount was funded by government bonds, the last of which were only paid off in 2015.

Managing these compensation pay-outs in St Vincent was every bit as complicated – and rigorously documented – as everything else to do with the process. Typical (Document X1o) was the £100 compensation given on 11 December 1833 to one Patrick Cruikshank for the ‘loss’ of ownership of his slave John, a carpenter on his estate.

Each slave had to be valued against the future loss of return on their owners’ original investment following the change in the law. St Vincent based appraisers John Le Gall & Gerrit Van Steyningen estimated that the former owner of a slave called Juliett would lose £64 – £7,800 in today’s money – in profits from her unpaid labour (Document X1k). On 2 December 1836 the appraisers confirmed this in writing and the owner was accordingly compensated. Juliett it is assumed, received nothing.

In fact, the passing of the Bill for the Abolition of Slavery on 26 July 1833 made only a nominal change to the actual rights of the enslaved. Under the new law, slaves on St Vincent, as elsewhere in the Caribbean, simply became ‘apprentices’ after 1 August 1834 – six years for field slaves, and four for house slaves.

These ‘Apprenticeships’ were harsh, prescriptive and in real terms no different from slavery, as they continued to bind the ‘freed’ slaves to their ‘former’ owners.

The biggest impact of the abolition of slavery came in the injection of the equivalent of billions of pounds of compensation payments into the British private sector. This drove the Industrial Revolution, the growth of Empire and ultimately the transformation of Britain into a trading and military behemoth made unchallengeable for the rest of the 19th century.

Juliett and her descendants did not do so well. Today the per capita GDP of the UK is five and a half times that of St Vincent & The Grenadines, as it now known. It is this that drives the protests and demands for reparations for slavery during this month’s royal visits to the Caribbean. They seek compensation that reflects the millions granted to slave owners in the 19th century, turned by 200 years of compound interest and return on reinvestment into trillions of pounds worth of legacy capital for 2022’s wealthiest Britons.

Some critics of reparations argue that setting a suitable amount of money in compensation for the descendants of Juliett would be impossible to calculate. It is true to say however that it would not be impossible to make a start. The original paperwork exists, and some of it is in Bexhill Museum.