Saxon Bexhill

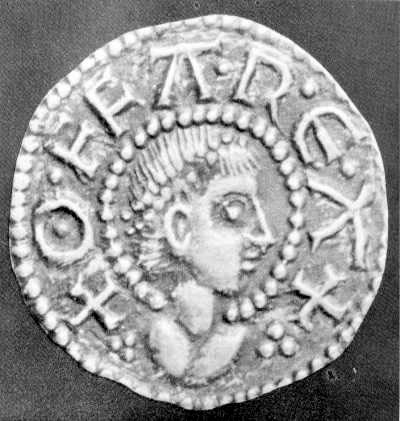

The first reference to Bexhill is in a charter of King Offa in 772AD. Some of the stone work in St. Peter’s Church is also believed to be Saxon.

There were certainly people living here before this time, but we know almost nothing about them.

The “Bexhill Stone” was discovered under the nave of St. Peter’s Church during extensive alterations in 1878. It is a fine example of Saxon stone work possibly dating to the late 9th or early 10th century. At first it was thought to be the lid of a child’s stone coffin, but is, probably, the lid of a reliquary, a box containing holy relics. It has been suggested that they might have been relics of St. Wilfred, although there is no direct evidence to support this. It is not clear if the church mentioned in 772 is St. Peter’s, as the land described does not appear to include the Old Town. The Domesday survey of 1086 mentions two churches; the location of the second one is unknown. Offa seems to be establishing a minster church in 772 which would serve a wide area. Such a minster would have had an elaborate reliquary like the Bexhill Stone.

The 772AD Bexhill Charter – from a medieval transcription.

“In the name of our Lord God and saviour. What is done for this world barely lasts until death, but what is done for eternal life remains forever after death. Therefore it is for everyone with deep forethought of mind to ponder and consider how with the fleeting possessions of this world he may obtain for his treasure the abodes of heavenly promise. Wherefore I, Offa, King of the English, for the good of my soul and for the love of God, and in accordance with my former promise grant in eternal possession to Almighty God and the venerable Bishop Oswald [of Selsey 765-780] a certain piece of land in Sussex for the building and endowing there of a minster church so that it may be seen to serve the praise of God and the honour of the saints, that is, 8 hides in the place which is called Bexhill [Bixlea] as set forth in the bounds.”

“These are the bounds of the 8 hides of inland of the people of Bexhill. Firstly at the servants’ tree, from the servants’ tree south to the treacherous place, so along the shore over against Cooden Cliff, eastwards and so up on to the old boundary dyke, so north to Kewhurst, and so to the Benetings’ stream, and so north through Shortwood to the boundary beacon, from the beacon to the bold men’s ford from the ford along the marsh to the road bridge, from the bridge along the ditch to Beda’s spring, from the spring south along the boundary thus to the servants’ tree.”

“These are the gavolland of the outland of Bexhill, in these places which are called by these names: At Barnhorn 3 hides, at Worsham 1 hide at Ibba’s wood 1 hide, at Crowhurst 8 hides, at Ridge 1 hide, at Ghyllingas 2 hides, at Foxham and Blackbrooks 1 hide, at Icklesham 3 hides; with all things pertaining thereto, fields, woods, meadows, fishponds. Let the aforesaid land remain from this day, given through me as I have said in the name of God, free from all royal extraction and bound to the use of those serving God, but on this condition: that after his day, this gift is returned to the episcopal see which is Selsey. If anyone at any time in great or small degree dares to reduce this gift made by me, let him know that he will incur the penalty for his presumption in the stern judgement of the all-powerful God, and will not escape from a bad hearing.”

“These are the bounds of Icklesham, to the pool in the hollow of the cliff, out on the middle of the brook, so to Tatta’s corner of land, to the moor, to Eadwine’s valley as far as the boundary of Kent, then west along the middle of the bathing brook.”

“This Charter was written in the year 772 from the incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ, the 10th indiction, on the 15th day of the month of August. I, Offa King of the Mercians, as the power was conceded to me by God who reigns, have confirmed the Charter of gift, signing it with my own hand, and placed the sign of the holy cross. I, Ecgberht King of Kent, have agreed and signed. I, Jaenberht, archbishop [of Canterbury 765-792] by the grace of God have signed. I Cynewulf, King of the West Saxons, have agreed and signed this gift. I, Eadberht, bishop [of Mercia 764- 781], have agreed and signed. I, Oswald, bishop [of Selsey 765-780], have signed the gift made to me. I, Righeah, bishop, have agreed. I, Diora, bishop, have signed. I, Oswald, Lord of the South Saxons, have agreed. I, lord Osmund, have agreed. I, lord Aefwald, have acquiesced. I, lord Oslac have consented. And these witnesses were also present whose names are written below: Abbot Botwine, Eata, Heabercht, Borda, Berhtwald, Esne, Huithyse, Baldraed, Bryne, Stridberht, Cyne, Ealdred, Lulling, Berht, Byrnbere, all the shire and Aemele, prefect. All these agreed, signed, and confirmed.”

“These are the land boundaries of Barnhorn, firstly at the mossy spring, from the spring south into the valley, from the valley up to the little heath, to the goblin’s spring, so south and east to the old road, along the road to the old boundary mark which stands by the side of the road, to the deep valley, to the reed pond. From the pond to the five roads, and south to the red ditch, along the ditch to the Picknill [Picknoll] and so south to Cylla’s Hill, from the hill to Cylla’s spring, west along the stream to Thunor’s clearing, and so west along the stream on the outside of the saltmarsh, and so north to the black brook, up along the stream to the swine enclosure. North along the boundary to the slaughter pit, and so north to the muddy ford, and so on up to the old dyke, and thus to the mossy spring.”

1066 – Bexhill and the Conquest

The 1066 invasion was due to a disagreement over who would succeed Edward the Confessor as King of England, the Kingdom was given to Harold Godwinson by the Saxon nobles although William of Normandy claimed to have been promised the crown. The invasion fleet landed on the coast around Pevensey. William defeated King Harold on the 14th October, 1066 at the Battle of Hastings and was crowned King of England in Westminster Abbey on the 25th December, 1066.

In 1085, William ordered the Domesday Survey of England which was completed in 1086. This recorded the value of manors within England and Bexhill is described thus:

“In Bexhill Hundred Osbern holds Bexhill from the Count [of Eu]. Before 1066 Bishop Alric held it because it is the bishopric’s; he held it later until King William gave the castelry of Hastings to the Count. Before 1066 and now it answered for 20 hides. Land for 26 ploughs. The Count [of Eu] holds 3 hides of the land of this manor himself in lordship. He has 1 plough; 7 villagers with 4 ploughs. Osbern has 10 hides of this land; Venning 1 hide; William of Sept-Meules less ½ virgate; Robert St. Leger 1 hide and ½ virgate; Reinbert ½ hide; Ansketel ½ hide; Robert of Criel ½ hide; the clerics Geoffrey and Roger 1 hide in prebend; 2 churches. In lordship 4 ploughs; 46 villagers and 27 cottagers with 29 ploughs. In the whole manor, meadow, 6 acres. Value of the whole manor before 1066 £20; later it was waste; now £18 10s; the Count’s part 40s thereof.

Osbern holds 2 virgates of land from the Count [of Eu] in this Hundred. It always answered for 2 virgates. He has 5 oxen in a plough. The value was 8s; now 16s.”

The knights in William’s army were rewarded with land in England and so replaced the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy. Bexhill manor was owned by the bishops of Chichester but William took it away and gave it to Robert Count of Eu.

The phrase ‘later it was waste’ may suggest that Bexhill was destroyed during the Norman Conquest. This may have been while William was moving his army between Pevensey and Hastings, possibly going through Bexhill and destroying it in the process. Another, probably more likely, explanation was that the Norman army raided the surrounding countryside after taking over Hastings, this would have prevented a local up-rising and also force Harold to move his army South, to fight a battle on William’s terms, rather than taking a defensive position further up-country, which would be harder for the Normans to take.

There is also mention of two churches in Bexhill, one is certainly St. Peter’s Church but it is not known where the second one was. A Norman tower was added to St. Peter’s after the Invasion.

During the Norman Conquest of 1066 it appears that Bexhill was largely destroyed. The Domesday survey of 1086 records that the manor was worth £20 before the conquest, was ‘waste’ in 1066 and was worth £18 10s in 1086. King William I used the lands he had conquered to reward his knights and gave Bexhill manor to Robert Count of Eu, with most of the Hastings area. Robert’s grandson, John Count of Eu, gave back the manor to the bishops of Chichester in 1148 and it is probable that the first manor house was built by the bishops at this time.

The later manor house, the ruins of which can still be seen at the Manor Gardens in Bexhill Old Town, was built about 1250, probably on the instructions of St. Richard, Bishop of Chichester. The Manor House was the easternmost residence owned by the bishops and would have been used as a place to stay while travelling around or through the eastern part of their diocese.

There were often disputes between the Bishops of Chichester and the Abbots of Battle Abbey, usually about land ownership in this area. In 1276 a large portion of Bexhill was made into a park for hunting and in 1447 Bishop Adam de Moleyns was given permission to fortify the Manor House.

Queen Elizabeth I

In 1561 Queen Elizabeth I took possession of Bexhill Manor and three years later she gave it to Sir Thomas Sackville, Earl of Dorset. The Earls, later Dukes, of Dorset owned Bexhill until the mid 19th century. Their main residences were Buckhurst Place in Sussex and Knole House in Kent.

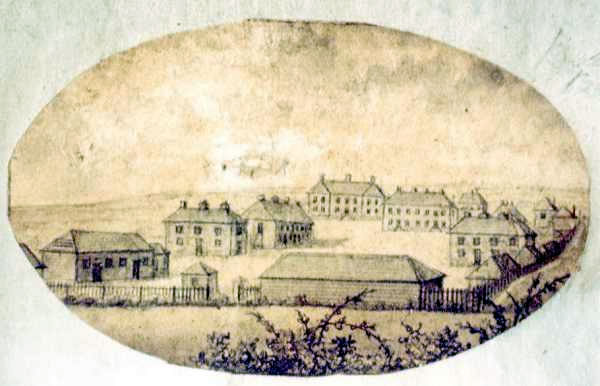

In 1804 soldiers of the King’s German Legion were stationed in barracks at Bexhill. These troops were Hanoverians who had escaped when their country was overrun by Napoleon’s French army, As King George III was also the Elector of Hanover, he welcomed them and they fought as part of the British army.

In 1804 soldiers of the King’s German Legion were stationed in barracks at Bexhill. These troops were Hanoverians who had escaped when their country was overrun by Napoleon’s French army, As King George III was also the Elector of Hanover, he welcomed them and they fought as part of the British army.

At about this time, defensive Martello Towers were built along the south east coast, including Bexhill, in order to repel any French invasion. In 1814 the soldiers of the King’s German Legion left Bexhill and played an important part in the Battle of Waterloo the following year.

The German troops had been here to protect Bexhill from the French.

However, many of the local people were actively trading with the enemy by way of smuggling. The best known of the local smugglers were the Little Common Gang and the most famous incident was the Battle of Sidley Green in 1828.

Earls De La Warr

In 1813 Elizabeth Sackville had married the 5th Earl De La Warr, and when the male line of the Dukes of Dorset died out in 1865 the land passed to the Earls De La Warr.

It was the 7th Earl De La Warr who decided to transform the small rural village of Bexhill into an exclusive seaside resort. He contracted the builder, John Webb, to construct the first sea wall and to lay out De La Warr Parade. Webb, in part payment for his work, was given all the land extending from Sea Road to the Polegrove, south of the railway line. Webb was instructed to build the shops on his land as Earl De La Warr did not want his visitors mixing with ‘trade’.

Opened in 1890, the luxurious Sackville Hotel was built for the 7th Earl De La Warr and originally included a house for the use of his family. In 1891 Viscount Cantelupe, his eldest surviving son, married Muriel Brassey, the daughter of Sir Thomas and the late Annie, Lady Brassey of Normanhurst Court near Bexhill. The Manor House was fully refurbished so that Viscount and Lady Cantelupe could live in style as Lord and Lady of the Manor. Finally, the 7th Earl De La Warr transferred control of his Bexhill estate to Viscount Cantelupe.

When the 7th Earl De La Warr died in 1896 Viscount Cantelupe became the 8th Earl De La Warr. At this time he organised the building on the sea front of the Kursaal, a pavilion for refined entertainment and relaxation. He also had a bicycle track and cycle chalet made at the eastern end of De La Warr Parade. These amenities were provided to promote the new resort. Meanwhile, many independent schools were being attracted to the expanding town due to its health-giving reputation.

Arrival of the Railway

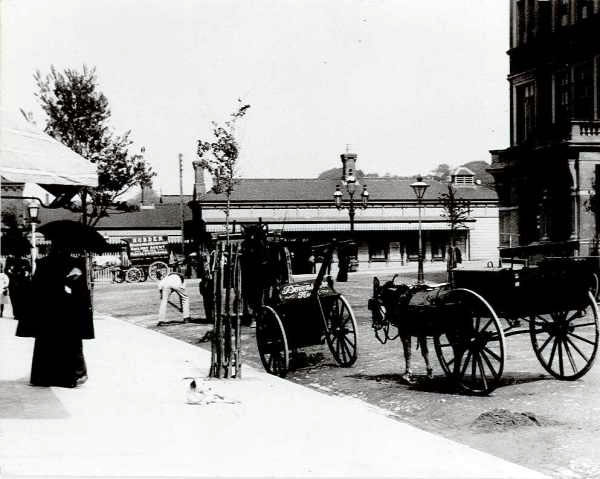

The railway came through Bexhill in 1846, the first railway station being a small country halt situated roughly where Sainsbury’s car park is today. This was some distance from the village on the hill. A new station, north of Devonshire Square, was opened in 1891 to serve the growing resort. In 1902 the current railway station was opened and the Bexhill West Station was built for the newly built Crowhurst Branch Line.

The railway came through Bexhill in 1846, the first railway station being a small country halt situated roughly where Sainsbury’s car park is today. This was some distance from the village on the hill. A new station, north of Devonshire Square, was opened in 1891 to serve the growing resort. In 1902 the current railway station was opened and the Bexhill West Station was built for the newly built Crowhurst Branch Line.

1902 was the year that Bexhill became an Incorporated Borough. This was the first Royal Charter granted by Edward VII. Bexhill was the last town in Sussex to be incorporated and it was the first time a Royal Charter was delivered by motor car. To celebrate the town’s newfound status and to promote the resort, the 8th Earl De La Warr organised the country’s first ever motor car races along De La Warr Parade in May 1902.

In 1902 the town was scandalised at this time by the divorce of Earl De La Warr. Muriel had brought the action on the grounds of adultery and abandonment. She was granted a divorce and given custody of their three children. Muriel, with her children, Myra, Avice and Herbrand, went back to live with Earl Brassey at Normanhurst Court. The 8th Earl De La Warr re-married but was again divorced for adultery. He also suffered recurrent and well-publicised financial difficulties. At the start of the First World War in 1914 the Earl bought a Royal Naval commission. He died of fever at Messina in 1915.

Herbrand Edward Dundonald Brassey Sackville became the 9th Earl De La Warr.  He is best known for championing the construction of the De La Wan Pavilion, which was built and opened in 1935. The 9th Earl also became Bexhill’s first socialist mayor in 1935/1935. He died in 1976.

He is best known for championing the construction of the De La Wan Pavilion, which was built and opened in 1935. The 9th Earl also became Bexhill’s first socialist mayor in 1935/1935. He died in 1976.

The Second World War caused the evacuation of the schools and caused substantial bomb-damage to the town. Many schools returned to Bexhill after the war but there was a steady decline in the number of independent schools in the town. The break-up of the British Empire and in particular the independence of India in 1947 hastened the process. Most of the schools were boarding and catered largely for the children of the armed forces overseas and of the colonial administration.

Although the number of schools decreased many of the parents and former pupils had fond memories of the town and later retired to Bexhill. Schools and tourism had been the sources of the town’s prosperity.

From the 1960s the town began to lose its appeal as a seaside resort and became more residential in nature. This, combined with the loss of the many independent schools, severely affected the local economy.