From: – “The Law Society’s Gazette”, Wednesday, 19th Decenber 1984 (pages 3572 & 2573)

Smuggling Informers

by Sancha de Una (Historian)

Two-and-a-half centuries ago a handful of counties in Great Britain were overrun by powerful gangs which had the support of much of the community and which, despite the presence of special officers and troops, regarded the law with contempt and held complete dominion in their own territories. To smash these organisations the government of the day decided that the only solution was to encourage `supergrasses’.

Smuggling tea and other luxury goods on which import duties were high was the business of these gangs and Kent, Sussex and parts of Dorset their domain. Demand for the goods was great and the profit to be made enormous. The leaders were shrewd businessmen who could build warehouses and mansions with the cash from their industry and who did not consider themselves common malefactors; they described themselves as ‘free-traders’.

For the most part the smugglers came into conflict only with prison staff and with customs officials (riding officers), whose job was to keep suspects under surveillance, to prevent the landing of contraband and to confiscate hidden goods. Though troops were sent into southern England to assist the customs men, little impression was made on the smuggling industry. The gangs had muscle to flex, and on several occasions battles were waged between smugglers `working’ cargoes and the customs officials and dragoons intercepting them.

Only the farmers had a genuine grievance against the smugglers who hired men who would otherwise be labourers, and who `borrowed’ farmers’ horses to exhaust them working a cargo. So long as they turned a blind eye the masses supposed themselves safe from the threats of violent punishment and death frequently meted out to customs men.

It was not this ever-present threat of violence to its officers that most angered the government — it was the massive loss of revenue which the customs duty would otherwise have raised to fund wars abroad (a large slice of which went to line the pockets of unscrupulous Ministers). What irritated the government almost as much was the smugglers’ habit of carrying letters abroad, `improper correspondences’, to enemies of Britain, especially the exiled Jacobites.

Act of Indemnity

The decision to encourage informers in order to break the smuggling trade was taken in 1736 on the recommendation of a Parliamentary Committee of Inquiry headed by Sir John Cope. Cope was alarmed that the tentacles of the business, in the shape of large, heavily-armed cavalcades, were reaching the capital itself, and that vast numbers of people were aiding and harbouring the villains. The result was the Act of Indemnity for Smugglers.

The indemnity applied to those smugglers willing to betray their colleagues. Despite the dangers inherent in informing on the gangs, the offer of a total amnesty might appear tempting to a smuggler deeply implicated in past crimes, especially one held in custody.

All he need do was confess his misdemeanours in a sworn statement, and give the names and crimes of as many of his ex-comrades as he could remember. This done he was a free, and indemnified, man. If convictions were gained by his information he may even have been well rewarded with a cash handout. On the other hand, should the informer then return to smuggling (assuming the gangs would once again accept him) he stood to be in even deeper trouble than before if apprehended. He would be judged as a second, not a first offender, and could be tried for all the offences to which he had previously confessed and been pardoned. He would then be certain to hang, as opposed to being transported (transportation was no real threat to smuggling gangsters who frequently bought their way out of the hulks while waiting to leave the country).

This, then, was the theory behind the so-called ‘Smugglers Act’. The practice was somewhat different. It became an Act that was applied infrequently, as the community, as well as the smugglers themselves, were either too much in awe of the gangs, or too much in favour of them to do them harm. Richard Ashcraft had the distinction to be `the first smuggler convicted under the late Act’.

First Informer

The first substantial informer was Goring (probably an alias), who was an intimate of the people he betrayed and seems to have been motivated more by malice, especially against one Cat, rather than by a desire to come clean. Speaking of a battle between the Groombridge smugglers and the customs officials at Bulverhythe, Sussex, in 1737, in a long letter still extant, Goring gave particulars and names of those involved, and added:

`I will send a list of. . . the places’ names where they are usually and mostly resident… All were Sussex men, and may easily be spoke with . . . When once the Smuglers are drove from home they will soon all be taken… There were several young Chaps with the Smuglers, whom, when taken, will soon discover [ie name] the whole Company… Do but take up some of the Servants, they will soon rout the Masters, for the Servants are all poor.’

Nothing is recorded as to the eventual fate of the people mentioned in Goring’s intelligence, though the Groombridge smugglers lost their position as a triumphant and immune gang at about this time so it would seem that the supergrass, Goring, proved effective.

The demise of the Groombridge men, however, was overshadowed by the swift and bloody rise of the notorious Hawkhurst Gang. Their leaders were powerful, wealthy and intransigently cruel. With the smugglers of West Sussex, and the Chichester district in particular, they rose despite the presence of the Act of Indemnity, and cultivated a harsh policy towards would-be sneaks. They issued a general death threat against informers. Many innocents disappeared without trace, while several grasses escaped smugglers’ ambushes, even though their corrupt riding officer guards had been paid by the gangs to abandon their charges.

Gazetting

The most important amendment to the Smuggling Acts was introduced in 1746, and became known as the process of `gazetting’. The Law Dictionary of 1775 stipulates that, having been told of a smuggler accused by an informer, the King `may make an order requiring the offender to surrender himself in forty days after publication thereof in the Gazette, and in default thereof, the order being published twice in the Gazette, and proclaimed in two markets near where the offence was committed, and a copy thereof affixed up in some publick place there, the offender shall be attainted of felony and suffer death’. What this meant was that, having been accused by an informer, a man (and he need not actually be guilty — the grass’s word was all that was needed to brand him) who failed to surrender himself after gazetting had committed himself to being hanged. Trials for smuggling crimes could, in theory, be entirely overlooked, and with them the gangsters’ all too frequent habit of buying off or threatening juries. It would be hard to acquit a man who had patently refused to come forward once proclaimed.

The grip of the Hawkhurst Gang was generally so secure that gazetting caused little trouble to the majority of them. However, its immediate effect was hardly what the government could have intended. Informers bold enough to name smugglers put not only themselves at risk, but indirectly endangered other members of the community. Once gazetted and forced from their ‘steadies’, or normal places of abode, smugglers going into hiding were unable regularly to attend the coastal ‘workings’, and therefore took to other means of making a living; the incidence of highway robbery and armed housebreaking rose dramatically.

In 1747 a chain of events was triggered that ultimately ruined the Hawkhurst Gang, and while supergrasses played a crucial part in this, they may not have come forward so freely if the smugglers’ brutality had not finally alienated the community.

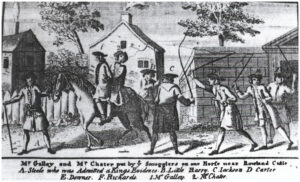

Daniel Chater, an innocent old shoemaker, was called to be a reluctant witness against John Dimer, a smuggler who had taken part in a raid on Poole custom house. Accompanied by a customs official, William Galley, Chater set off to see the local magistrate. On the journey the couple lost their way, and had the misfortune to ask directions at a smuggling inn. That night Galley and Chater were severely whipped and beaten, and Galley was buried alive, though unconscious, in a sand pit. Chater was detained for several days in the turf-house of the infamous Mills family, and, after torture, was eventually flung down a dry well and pelted with rocks and gate posts. Ostensibly the gang committed this crime to ‘put out of the way’ witnesses against their comrade.

Daniel Chater, an innocent old shoemaker, was called to be a reluctant witness against John Dimer, a smuggler who had taken part in a raid on Poole custom house. Accompanied by a customs official, William Galley, Chater set off to see the local magistrate. On the journey the couple lost their way, and had the misfortune to ask directions at a smuggling inn. That night Galley and Chater were severely whipped and beaten, and Galley was buried alive, though unconscious, in a sand pit. Chater was detained for several days in the turf-house of the infamous Mills family, and, after torture, was eventually flung down a dry well and pelted with rocks and gate posts. Ostensibly the gang committed this crime to ‘put out of the way’ witnesses against their comrade.

A few weeks before, one of the Mills’ sons, John, had, with three Hawkhurst men, whipped to death a labourer whom they accused of stealing run tea. When the corpse was found soon afterwards, the dead man’s in-laws, although they knew the identities of the culprits, remained silent. The atrocious deaths of the three shocked southern England, but no-one was apprehended for over a year.

Breakthrough

Then came the breakthrough. In September 1748 an anonymous letter, pinpointing the burial site of Galley, was delivered to ‘persons of distinction’. Soon after followed another, pointing out that one William Steel was involved in the murders, and where he might be apprehended. The identity of this informer has never been revealed.

Steel, once in custody, faced the choice of becoming an ‘evidence’, or the prospect of the noose. Not surprisingly, he decided to turn supergrass. Gradually, the details of the murders and the names of those concerned came to light, and, as many of the most notorious Hawkhurst and Sussex leaders were involved, the authorities were glad to round up as many as possible. Only a handful managed to flee abroad. In the circumstances the smugglers were unlikely to blame Steel, but another culprit, John Race, became an anathema to them when, to save his neck, he volunteered himself as an ‘evidence’. On the other hand, those who remained silent in captivity included a John Hammond who had often said publicly he thought it no crime to do away with informers, while Richard Mills denied his part in it, but added he ‘should not have thought it any crime to destroy such informing rogues’ as Chater.

Jacob Pring, though a gangster not implicated in the murders, volunteered himself as informer and even suggested ‘he seek out certain smugglers in hiding. John Mills and several others were lured into a trap by their old colleague and despite violent resistance, were secured by dragoons. When urged Mills retorted that he would ‘merit damnation’ if he informed on his ‘companions’.

In all, over 14 reputed (and mostly gazetted) smugglers were tried and hanged (and others transported) in 1748 and 1749, due to information received in connection with the murders and the Poole raid. The government was satisfied that it had eliminated the renowned leading gangsters and that justice had been seen to be done. It is worth remembering, however, that history has only the word of the informers that some of the men convicted were actually connected with these crimes. Informers often acted out of malice and fear for their own lives. The Hawkhurst Gang was crushed, or at least driven underground. Only occasionally did smugglers carry out their business publicly with impunity. But ‘free trading’ remained rife while duties on certain goods remained high, and while it continued, informers posed a threat, not only to the smuggler, but indirectly to those who willingly or inadvertently saw too much of the smugglers’ business. The Smugglers Act was modified in 1779 and 1784, and totally revised in 1826. Smuggling itself was only reduced into insignificance by the lessening of import duties commenced by Pitt.

Suggested further reading: Sussex Smugglers: The Genuine History of the Inhuman and Unparalleled Murders of Mr William Galley, a Custom House Officer, and Mr Daniel Chater, a Shoemaker, by Fourteen Notorious Smugglers, Anon, 1749 (Reprint, Gibbings and Co, London, 1900).