AIR RAID PRECAUTIONS & CIVIL DEFENCE

The nineteen thirties were an unsettled decade, with war seemingly more and more likely. Air Raid Precautions (ARP) was set up in 1937 dedicated to the protection of civilians from the danger of air raids. Every local council was responsible for organising ARP wardens, messengers, ambulance drivers, rescue parties, and liaison with police and fire brigades.

Bexhill was quick off the mark in the February of 1937 with a well-attended public meeting at the De La Warr Pavilion and at the beginning of 1938 The Air Raid Precautions Act came into force. Which compelled all local authorities to begin creating their own ARP services. Bexhill was ready and had recruited both men and women under the age of 60.

The roles were:

Air Raid Wardens. The streets were their domain ensuring the public took cover during air raids, made sure the blackout was complied with and reported incidents to the Report Centre

Report Centre. This was the control room that monitored and controlled the response to raids.

Messengers – Back up if bombing disrupted normal telephone links.

First Aid Parties. – First responders to those injured in air raids.

Ambulance drivers. – For the transmission of the wounded to first aid and hospital facilities,.

Rescue Parties – Responsible for the heavy work involved in extracting the wounded and the dead from bombed buildings. Not open to women.

Gas decontamination. – Specialist roles in dealing with gas and chemical attacks. Not open to women.

Fire Guards. – This role came later in 1941 as a response to incendiary bombs.

Public education was carried out through the Bexhill Observer, which, in May through July of 1938, printed a series of articles aimed at telling householders  how they could adapt their homes to mitigate the effects of bombing. So thorough was public education that WD & HO Wills issued a cigarette card album entitled Air Raid Precautions which covered house adaption, incendiary bombs, fire-fighting, gas masks and contamination and air defence.

how they could adapt their homes to mitigate the effects of bombing. So thorough was public education that WD & HO Wills issued a cigarette card album entitled Air Raid Precautions which covered house adaption, incendiary bombs, fire-fighting, gas masks and contamination and air defence.

In the October the Observer printed a list of names and addresses of wardens.

During 1939 the level of preparedness increased with a series of exercises. In January to test the Little Common wardens’ incident reporting abilities. In February a far more comprehensive effort including rescue [Albany and Amherst Roads], a plane crash [Woodville Road], car collision [Devonshire Road], exploded petrol tanks [Ninfield Road], fractured gas main [Brockley Road] and looting. 80 wardens and 100 ARP workers involved, all being unaware of the planned incidents.

During March rescue of casualties was practiced. The Observer jocularly remarked:

The work of the rescue parties was efficiently carried out, due care and consideration being shown towards the dummies, each of which, when rescued, was found to be in a state of collapse. Efforts of resuscitation, however, proved of no avail, in spite of the methods employed by the highly trained personnel.

It was Cooden and Little Common’s turn for the same in June, but in July Bexhill participated in a black-out exercise all across South East England from 11pm to 2am. Fire fighting and rescue, first aid parties and public utilities. The public were asked to stay inside and not hamper proceedings. It went very well. Fireworks were used to simulate bombs. Useful to the exercise was an actual gorse fire on the Down – which had to be tackled in darkness. Intermingled with this were folk returning from a fair held there. In addition some 140 Territorial gunners and their guns were gathered at the station to go off to their summer camp. 600 Bexhill ARP volunteers were involved.

On the eve of war, in the August, another exercise was carried out over two nights. The voluntary black out effort by householders was particularly effective. E L Marriott, the Town’s ARP Officer was reassured by the level of preparedness achieved, only a grave shortage of wardens around Reginald and Salisbury Roads gave concern. The First Aid Centre at the athletic club was not yet ready so the outpatients department of Bexhill Hospital was used.

Other eve of war preparations were the masking of traffic lights in Western Road and Belle Hill and white lines painted on kerbs. The ARP system was manned day and night. Grocers reported big increases in the sale of canned foods. Also in demand were candles, torches and tape for screening windows.

In the November the distribution of babies’ gas helmets took place. 440 were issued from 6 depots. Each helmet weighed 6 lbs and cost £1 to produce.

In the December the seven sirens in the town were tested and would be once a month.

Exercises continued during 1940 during February and April. With the Phoney War ending with the German Blitzkrieg in May, the Local Defence Volunteers kept the Report Centre under guard. Those within had a length of lead pipe for defence. Come the September the populace was becoming used to bombing raids but on one occasion there was some alarm and confusion amongst the population as an electricity failure to the sirens meant that the All Clear could not be sounded. So wardens in the streets rang hand bells. Some members of the public thought that a gas attack was taking place or that an invasion signal was being raised.

On the 26th of September the Town Hall was hit by a bomb and the Report Centre was disrupted. Reginald Bridgeland, a member of Team B, recalled: We all dived into our strong room, the shriek of bombs sounding above the noise we made. Scarcely had we plunged in & pulled the door to behind us, than one shriek detached itself from the rest & grew into a terrific scream, followed immediately by a colossal bang, & for a few moments the whole strong room seemed to rock & everyone experienced a sensation of utter darkness. Then books & files fell on top of us from the shelves whilst the noise of bricks & debris falling on the roof of the room was deafening. After a few seconds this ceased & we realised with thankfulness & amazement that we were all unhurt although on looking up we saw that the roof of the strong room had been wrenched away from the walls & had moved bodily several inches. We afterwards discovered that the room had also moved several inches from its foundations. On trying the door we found it would open only a few inches, as it was blocked by debris from outside. Somebody came along & having ascertained that we were all O.K (much to their astonishment) said that they would soon have us out.

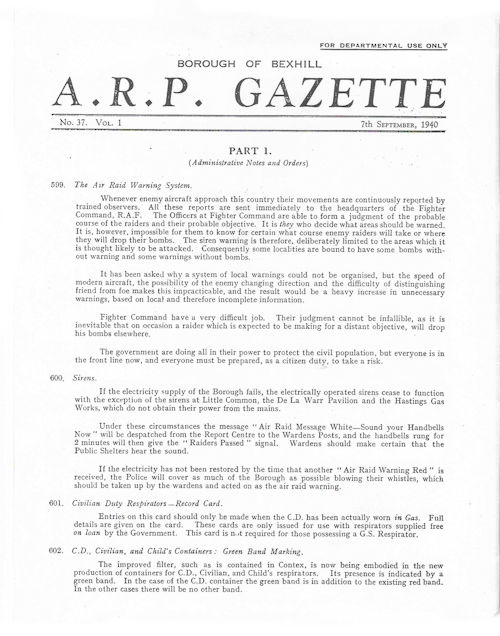

There had been criticism of the air raid warning system. Some comment was made as to whether or not there should be local alarms as there had been warnings without bombs and sometimes bombs without warnings. Alerts originated from RAF Fighter Command. A scheme for local warnings submitted to Regional Office. This comprised 12 inch bell gongs in the town centre, with an audible range of 150-200 yards, worked electrically. Alerts originated from the local Observer Corps.

The bell gong system was tested in February 1941. The gongs were sited at the junction of Sea Road and Station Road, junction of Parkhurst Road and Devonshire Road and Marina at the bottom of Devonshire Road. The plan was to start with 15 installations perhaps increasing to a total of 25. The alarm was signalled by an interrupted ringing and the all clear by a continuous ring. The same month Air Raid Precautions changed its name to Civil Defence and a uniform was introduced, replacing civilian clothes. This was a dark blue battledress and trousers for men and a serge tunic with trousers or skirt for women.

March 1941 was a busy month. The Report Centre moved to Garth Place. Gas attack were still considered a risk and the Mayor appealed to the public to wear their gas masks for 10 minutes every Saturday at 11am. A gas conditions exercise was carried out with members of Civil Defence doing their duties wearing respirators for half an hour. The public were also encouraged to follow suit, but few did.

Miss E Butler of Camperdown Street kept a tally of warnings and as of 1:25pm 20th March she had logged 444 warnings.

Rescue became a priority for exercises. The Metropole Hotel was used in May and the Down School in June. In this exercise the messenger service was put into actual use due to a telephone failure

April 1942 saw a big exercise on a large scale involving Home Guard and military units and a rescue party from Eastbourne. Actual bombed sites were used. The scenario of coping with unexploded bombs was tried. 279 messages were handled by the Report Centre. This was repeated in December by a very successful all day effort based on rescue and a gas attack. Actual bombed sites were used in Devonshire Road, Cantelupe Road and the Metropole Hotel.

The tip and run low level attacks had petered out in June 1943. Had they continued the populace would have had the advantage of a new air raid warning alarm installed in July, the Cuckoo Alarm. This system had been running successfully in Eastbourne for the past year. The alert tone was the cuckoo sound for one minute and the all-clear by a series of two second blasts.

Concern about gas never went away. In January 1944 notice was given that wardens would be calling door to door to inspect gas masks. Any defective masks could be repaired at the Sackville Road facility. The September turned out to be Bexhill’s first month entirely free of air raid warnings. The very last use of siren as a warning of hostile aircraft came in November. However sirens continued to be tested monthly and found a post war use as a call out for the Fire Brigade.

On the 3rd of May 1945 the public air raid warning system was discontinued and Civil Defence was stood down. In Bexhill there had been 1468 alerts and in addition the local alarm was sounded 557 times.

The Report Centre had been fully manned each day ever since the outbreak of war and logged 51 raids, 326 high-explosive bombs and 6 strafing attacks.

AIR RAID SHELTERS

AIR RAID SHELTERS

The story of Bexhill’s World War Two air raid shelters is one of playing catch-up with events against a background of strict control by the Home Office Air Raid Precautions organisation [ARP].

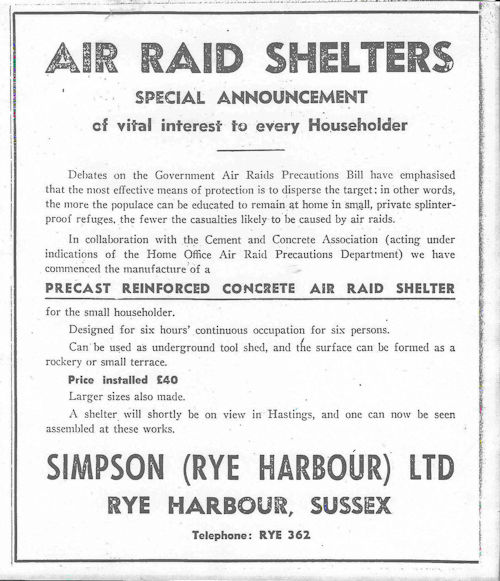

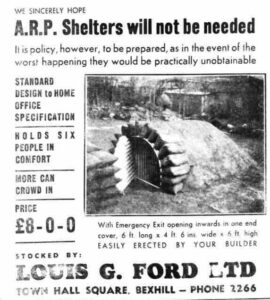

The Louis G. Ford advertisement on the right comes from a local newspaper, dated 2nd August 1939

The Ministry of Home Security produced a booklet, Your Home as an Air Raid Shelter, which gave individuals practical advice on how to adapt their dwellings to alleviate the effects of high explosive and incendiary bombs. It was thought that in the event of an air raid warning people would have 5 minutes to get home. For the 5% that could not, public shelters were to be provided.

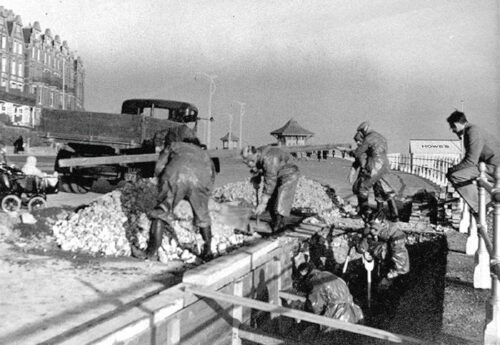

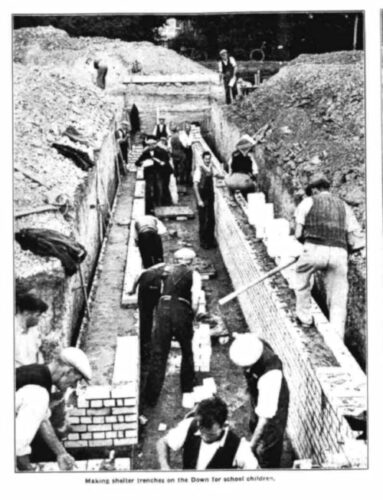

ARP authorised Bexhill Corporation to provide shelters for that 5% of the population at a cost of not more than £4 per head. As well as provision for schools to have trench shelters. By October 1939 the following public shelters had been built with the capacity as noted:

Amherst Road – Belle Hill – 40

Bending Crescent – 50

Channel View – 48

Chantry Lane – 70

Collington Halt [Cooden Drive] – 20

Colonnade – 150

De La Warr Road-Dorset Road – 35

De La Warr Road-Penland Road – 10

East Parade – 64

Holliers Hill – 40

Sidley Green – 135

Town Hall Square – 60

Upper Sea Road – 42

Wickham Avenue [Egerton Park] – 92

Wrestwood Road-St James’s Road – 70

At this period of the war Bexhill was a safe zone receiving evacuees from London. There was no expectation of the town becoming a target – so that with individuals urged to adapt their homes, and with poorer folk, earning less than £250 [later raised to £350] a year receiving council assistance in the form of loans and subsidised materials; no provision was made for the supply of the otherwise ubiquitous Anderson Shelter. By the August of 1940 when the whole of Southern England was open to aerial bombardment Andersons were no longer being made as the material was needed for other purposes. So Bexhill went without.

Just prior to Bexhill’s first bombing, shelter provision had been beefed up with a further six shelters. All was not well. The Bexhill Observer was critical of the council’s shelter provision. A reporter made a nocturnal tour and found five shelters letting in water and not fit for sleeping quarters. One shelter had actually been fitted out as a living room by an absent occupant.

By the end of 1940 Bexhill had been bombed 40 times and to meet the need, under Defence Regulations 23 and 50 authorisation was given to the council provide basement shelters. Eight basement shelters were involved, half of which were business premises in the town centre. The one under Miller and Franklin in St Leonards Road could house 200 people.

In the February of 1941 Morrison shelters were announced, to be supplied free to householders whose income was less than £350 per annum, or could be purchased for £7. They were not available for those who have previously had assistance with creation of a domestic shelter, nor for those who lived within easy access of a communal shelter. These shelters were essentially a steel framed rectangular box shape, for indoor use. By November Morrison applications totalled 837 and consideration was being given to supplying Morrisons to those whose domestic shelters were not up to standard.

As for the earlier scheme to support householders adapting their homes, only 420 applications had been made by March 1941. It was thought that lack of confidence by householders in their abilities was a major contributing factor.

Meanwhile the bombing continued and in May 1941 [actually as the Blitz was drawing to an end] six communal street shelters were built, all in residential areas. Each had places allocated to those in the neighbourhoods. Another six were planned. Another five shelters within existing properties were brought into use.

In the July a general overhaul of shelters was carried out with improvements to water supplies and sanitary facilities. An equipment inventory showed that light bulbs and biscuits [Crawford chocolate wholemeal biscuits] were particular targets of theft. During one week in September seven incidents, affecting five shelters, of light bulb theft were recorded.

No-one was ever caught thieving and it was impossible to keep every shelter under watch by police or wardens. In theory every shelter should have been checked twice daily, once at night, once during daylight.

In July 1943 the timber constructed Sidley Green shelter was replaced by a brick and concrete shelter and construction was underway of new type of school surface shelter immediately outside school premises at all schools.

Attacks on Bexhill now took the form of tip-and-run raids, small formations of fighter planes dropping a bomb and strafing. To counter this ten emergency street shelters each with a capacity of 20 were erected.

At war’s end the residents of Old Town were quick off the mark in petitioning for the shelter in Short Lane to be demolished. . Otherwise the council had to obtain permission from the Regional ARP Controller – taking into consideration danger to the public and traffic. The communal shelter in Victoria Road was removed with ARP Region permission as an experiment to ascertain cost. In the November 50 Commandos volunteered to dismantle the small shelters at the Central Station, Parkhurst Road and Collington Mansions.

In 1946 the Bexhill Observer raised the question of the lack of disposal initiatives for Morrison shelters, now unwanted scrap. By the August the council had been granted permission to collect all Morrison shelters that were issued free of charge. The shelters had to be in a dismantled state. Those wishing to retain these free-issued shelters could do so on payment of £1 10s.

[table id=30 /]