The Museum has taken the opportunity of the year 2000 to look back over Bexhill’s fascinating past and review some of the people, achievements and events that make the town so special.

The aim of this exhibition is to generate interest in Bexhill’s history and so stimulate interest in the town. We will be looking towards the future as well and will make some predictions as to where the town may be heading, for better or for worse. We do not have any crystal balls in the collection, and an understanding of the past does not necessarily provide any clues for the future. However, it can never do any harm to stop and think about where the town is heading, to identify the special qualities of Bexhill that are worth preserving and to spot any potential dangers before it is too late to avoid them. It is hoped that this exhibition will, eventually, form the basis of a local history gallery which will interpret Bexhill’s past.

It is not possible to cover all of Bexhill’s history, so this exhibition should be seen as edited highlights. There is no objective history and bias and error are bound to creep into the accepted history of the town. We have tried, so far as it is possible, to make this account of the history of Bexhill as reliable as the sources available allow. It is difficult to get an objective account of the events of today; it all depends on your sources of information and who you choose to believe.

Why is Bexhill the way it is?

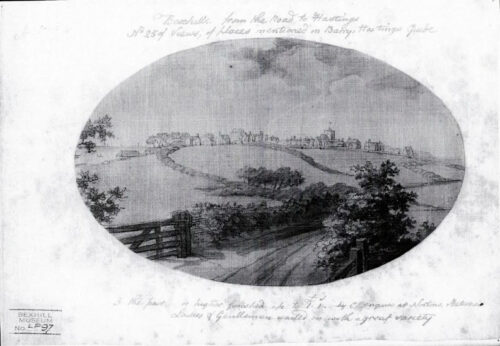

The settlements that were later incorporated into the borough were the villages of Bexhill, Sidley and Little Common. All were small rural communities whose economies were based on agriculture and supporting trades and industries. Despite being close to the sea, fishing was not a significant part of the local economy.

The settlements that were later incorporated into the borough were the villages of Bexhill, Sidley and Little Common. All were small rural communities whose economies were based on agriculture and supporting trades and industries. Despite being close to the sea, fishing was not a significant part of the local economy.

Bexhill village was important because it was the location of a “bishop’s palace” that was later known as Court Lodge and, finally, the Manor House. The building was more of a large house rather than a palace and was the eastern-most residence of the bishops of Chichester, who owned Bexhill Manor, and would have stayed there when travelling around the Episcopal see. The occasional presence of the bishops and their rating you would have added a touch of colour to what was otherwise a small rural community.

Ownership of Bexhill Manor passed from the bishops of Chichester to the Count of Eu, then back to the bishops, then to the Dukes of Dorset and, finally, the Earls De La Warr. None of these owners would have been resident in Bexhill but would have used the Manor House as a convenient stopping off point for journeys through the area and as a hunting lodge.

From 772 to 1883 the pace of change in Bexhill village would have been slow and gradual, but from 1883 the settlement exploded into a hive of activity. The 7th Earl De La Warr began to develop his Bexhill estate into a fashionable new seaside resort. Most of the central parts of Bexhill-on-Sea were built between 1883 and 1902. The resort was intended for a select and wealthy clientele and much was made of the health-giving properties of the area and water and the longevity of residents.

For the first half of the 20th century Bexhill-on-Sea was notable for the large number of independent schools here. Many of the schools cater for children of those involved with colonial administration and Armed Forces and so provided a link between the town and the British Empire. After the Second World War and, perhaps more importantly, after the break up of the Empire shortly afterwards many of the school was closed or moved away. From the 1960s, possibly as a result of cheap foreign holidays, Bexhill-on-Sea declined as a resort and became more residential in character.

Bexhill’s future

Understanding the past does not mean we can predict the future; past attempts to say what society will be like in 10, 50 or 100 years ahead have, usually, been very inaccurate. There is not a good reason to give up trying and so we walk suggests some alternative futures. “Unless we know where we have come from we cannot know where we are going”.

Optimistic view:

-

Regeneration

With a new-found interest and pride in Bexhill the Victorian heart of the town’s sensitively restored or redeveloped, new businesses relocate here and tourists/holiday makers flock to the town. Everyone is happy, except those residents who just want to be left alone.

-

Splendid Isolation

Bexhill is left in peace by the rest of the world, taxes are low but somehow the town is maintained in a reasonable condition. Everyone is happy, except those who need in employment, developing a business or relying on tourism.

Pessimistic view:

-

Bexhill-under-the-Sea

Sea levels continue to rise through a combination of climatic change and the land sinking. All that is left of Bexhill is the old town, the original Bexhill village, perched on top of the hill, overlooking the submerged resort. Fine views if you live in the Old Town, not so good for everyone else.

-

Decline and Degeneration

With no investment, little employment and no interest, the town is a squalid shell rife with drugs and crime. Bexhill has lost its identity and becomes a part of the urban sprawl that runs all along the south coast. A good setting for a science fiction film but not so good if we have to live here. The story begins here . . . . . . .

Prehistoric Bexhill

Jokes were once made concerning the initials of the Bexhill Corporation – B.C. but the history of the area does go back a very long way.

Dinosaurs

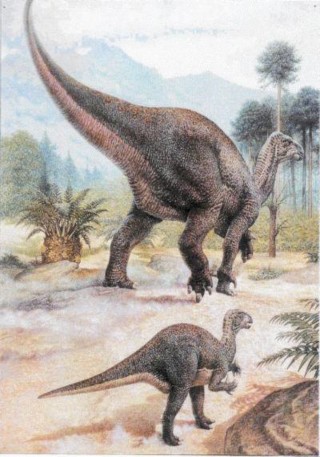

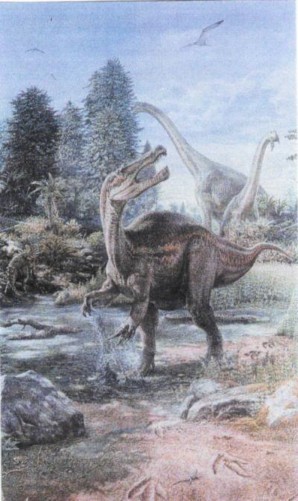

The rocks on which Bexhill stands are about 130 million years old. They contain the fossilised remains of plants and animals that inhabited the prehistoric landscape which was totally different from the one we are used to. Rather than being by the sea the area was freshwater floodplain dominated by rivers, lakes and swamps. There appears to have been a wet season and a dry season. The temperature would have been much higher than it is today and the presence of fossilised charcoal suggests that forest fires occasionally occurred.

The rocks on which Bexhill stands are about 130 million years old. They contain the fossilised remains of plants and animals that inhabited the prehistoric landscape which was totally different from the one we are used to. Rather than being by the sea the area was freshwater floodplain dominated by rivers, lakes and swamps. There appears to have been a wet season and a dry season. The temperature would have been much higher than it is today and the presence of fossilised charcoal suggests that forest fires occasionally occurred.

During the wet season, floods would wash bones that had been lying on the ground into the lakes and rivers and these were sometimes preserved as fossils. Vegetation consisted of coniferous trees, cycads, ferns and fern-like plants, there were, as yet, no deciduous trees and no grass.

The landscape would have been dominated by dinosaurs, and the most of the fossil remains that can be identified belonged to Iguanodon, a 5 to 10 metre long plant eating dinosaur. Bexhill is famous for the fossil dinosaur footprints that are sometimes exposed on the beach, most of these footprints have been attributed to Iguanodon. Remains have also been found of the armoured, plant eating dinosaur Hylaeosaurus and the meat eating Megalosaurus and Baryonyx as well as fragmentary remains of other small dinosaurs.

The landscape would have been dominated by dinosaurs, and the most of the fossil remains that can be identified belonged to Iguanodon, a 5 to 10 metre long plant eating dinosaur. Bexhill is famous for the fossil dinosaur footprints that are sometimes exposed on the beach, most of these footprints have been attributed to Iguanodon. Remains have also been found of the armoured, plant eating dinosaur Hylaeosaurus and the meat eating Megalosaurus and Baryonyx as well as fragmentary remains of other small dinosaurs.

The lakes and rivers were populated by various crocodiles, turtles, fishes, freshwater sharks, crustaceans and molluscs. On land there were insects and small mammals while the skies were still the domain of flying reptiles called pterosaurs.

Invaders and Settlers

Metalworking was introduced in the bronze age of 2,000BC – 700BC and the only evidence we have of this period is a small hoard of six copper alloy palstaves (axeheads) which were found at Culver Croft Bank, Cooden in 1892. These may have been buried for safe keeping by a travelling metalworker who did not want to carry too much heavy and valuable metal around the countryside or it’s possible they were buried as a sacrifice to the gods.

Metalworking was introduced in the bronze age of 2,000BC – 700BC and the only evidence we have of this period is a small hoard of six copper alloy palstaves (axeheads) which were found at Culver Croft Bank, Cooden in 1892. These may have been buried for safe keeping by a travelling metalworker who did not want to carry too much heavy and valuable metal around the countryside or it’s possible they were buried as a sacrifice to the gods.

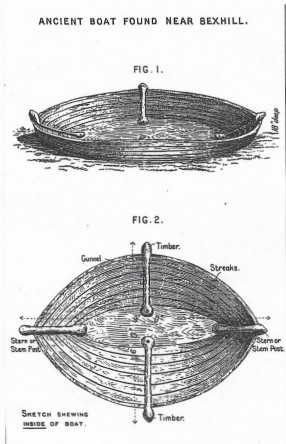

In 1887, an ancient boat was excavated from the beach off South Cliff – this was recorded by Charles Dawson, infamous for the Piltdown hoax, in the Sussex Archaeological Collections of 1894. The boat, if genuine, could have been prehistoric. Another, presumably ancient, boat was unearthed when Egerton Park was laid out in 1888.

The iron age of 700BC to 43AD is usually associated with a group of people known as the Celts. Very little material from this period has been found here, the nearest known site would have been the hill fort on East Hill in Hastings.

The Romano-British period of 43AD to 407AD saw a massive increase in iron production in this part of Sussex, the best known iron smelting or bloomery site was at Beauport Park just outside Hastings but there were bloomery sites at Sidley, Buckholt and Barnhorn. Some of the local iron working sites may have been in use prior to the Roman invasion of 43AD. An intriguing find that may date from this period is a carved stone head found in a garden in Wickham Avenue. It is made of pink granite and is shaped as the head of a man with florid hair and a beard. It is suggested that it might be Romano-British as it shows a mixture of Mediterranean and Celtic styles.

The prehistoric finds from Bexhill have mostly been stray surface finds with little or no archaeological context, the finds tell us that people were here in the distant past but we do not know where their settlements were or how they were using the landscape. The rapid development of the town over the last 115 years has covered or obliterated most of the archaeological evidence that we would need to attempt to decipher Bexhill’s ancient past.

The prehistoric finds from Bexhill have mostly been stray surface finds with little or no archaeological context, the finds tell us that people were here in the distant past but we do not know where their settlements were or how they were using the landscape. The rapid development of the town over the last 115 years has covered or obliterated most of the archaeological evidence that we would need to attempt to decipher Bexhill’s ancient past.

Humans have been in Britain for at least half a million years but the oldest evidence of people in this area dates to the Mesolithic or Middle Stone Age which was from 9,000BC to 4,500BC. These people were semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers who would move around their territory during the year exploiting various natural resources as they became available. We have examples of Mesolithic microliths from Bexhill; these are small blade-like pieces of flint that would have been assembled on a wooden shaft to form weapons and tools such as spears, harpoons and scrapers.

During the Neolithic 4,500BC to 2,000BC people began to farm the land rather than depending on hunting and gathering. These early farmers were in Bexhill as examples of polished flint axeheads and flint arrowheads have been found. In other part of the country these people built large burial mounds and ritual earthworks, but no such remains have been found here. In 1999 a very fine example of a late Neolithic barb and tang arrowhead was found at Broadoak Park.

Along the coastline is a submerged forest and the remains of trees and even hazelnuts are sometimes found at low water. These remains dated to the end of the Neolithic period and about 4,000 years old. The forest was submerged due to rising sea levels and the timber was preserved under the sand and mud.

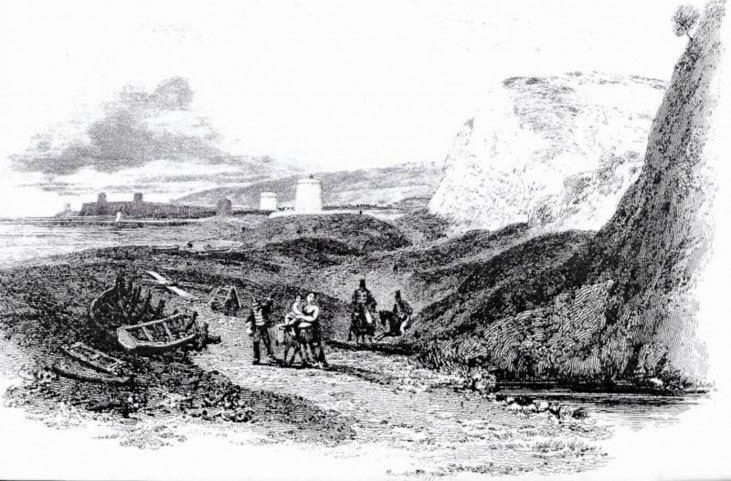

The Fort at Pevensey

The Romans built the first fort of Anderida (Pevensey) and, then, built a port on the same site. After the Romans left Britain it is said that Aella the Saxon landed at Selsey, West Sussex in 477, driving the Britons into the great forest of Andredsweald, which stretched from Kent to Hampshire.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that, in 491, Aella massacred the people of Pevensey who had taken refuge in the Roman fort.

Description of the fort

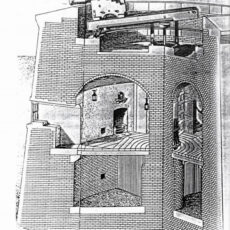

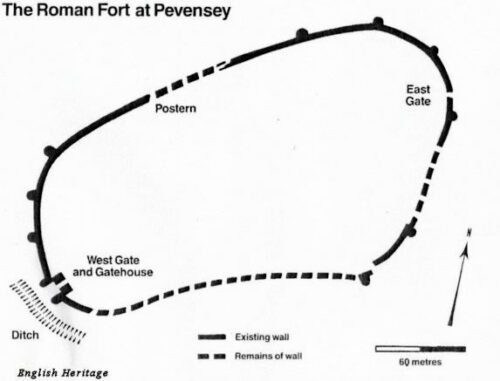

Early Roman forts were semi-permanent, elaborate constructions with two ditches, gates, palisade, and rampart towers made of wood. Once they had conquered most of Britain, they built more permanent castles in stone but still of a similar pattern. Like the early ones, these forts were usually square or ‘playing card’ shape, with large gates set in the middle of each side, so that troops could come out of the fort quickly to deal with any trouble. They built a string of such forts along Hadrian’s wall to keep out the Picts. The Romans did not expect to fight from these forts; they were confident enough to come out of them and fight an attacker in the open. Towards the end of the Roman period, however, when the Saxon shore forts were built, the basic design was modified, to give them the best defence against possibly superior forces, which they could no longer be absolutely sure of beating in the open. Anderita is a good example.

Early Roman forts were semi-permanent, elaborate constructions with two ditches, gates, palisade, and rampart towers made of wood. Once they had conquered most of Britain, they built more permanent castles in stone but still of a similar pattern. Like the early ones, these forts were usually square or ‘playing card’ shape, with large gates set in the middle of each side, so that troops could come out of the fort quickly to deal with any trouble. They built a string of such forts along Hadrian’s wall to keep out the Picts. The Romans did not expect to fight from these forts; they were confident enough to come out of them and fight an attacker in the open. Towards the end of the Roman period, however, when the Saxon shore forts were built, the basic design was modified, to give them the best defence against possibly superior forces, which they could no longer be absolutely sure of beating in the open. Anderita is a good example.

The walls are entirely made of stone and rubble, more than 3.6m thick (almost 12 feet) and originally they stood about 9m high (just under 30 feet). There are only two main gates: the East Gate, which is narrow by Roman standards, and the West Gate, which could be very heavily defended. Every part of the wall is overlooked by massive bastions designed for archery and artillery – they were very carefully placed so that no attacker could approach the wall without coming under fire.

The site was carefully chosen, not only to guard harbours and river entrances that might otherwise have been used by their enemies as invasion routes but also to be easily defended should those enemies appear in large numbers. At the time of building, the fort must have seemed impregnable and a great comfort to the Romano-British communities living nearby. And so it remained for

more than a century, sustained by manpower and supplies from the countryside around it. Only when the Saxons had taken possession of that countryside, and deprived those in the fort of essential supplies, were the defenders, finally, overcome. No castle or fort could hold out indefinitely in an enemy-occupied land. The Roman walls enclose an oval area of a little under 4 hectares (10 acres). The longer axis of this irregular shape runs from 800th-west to north-east.

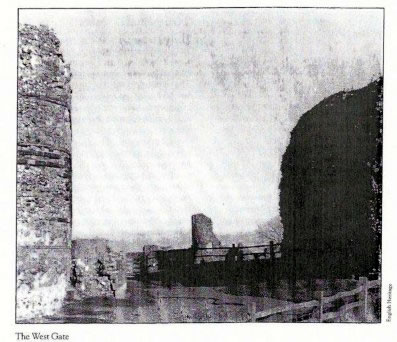

The West Gate and Gatehouse

Strictly, this is at the south-west of the fort, the only direction from which it could be approached by land. It is the main entrance to Anderida and was, probably, approached by a wooden bridge across the 5.5m ditch (18 feet) which separated the fort from the mainland.

Strictly, this is at the south-west of the fort, the only direction from which it could be approached by land. It is the main entrance to Anderida and was, probably, approached by a wooden bridge across the 5.5m ditch (18 feet) which separated the fort from the mainland.

Part of this ditch has been re-excavated and can be seen to the right of the entrance. Going into the fort, the bastion on the left-side still stands up to parapet level while the one on the right is rather lower. Little can now be seen of the gatehouse, which was attached to the inner walls of the bastions. However, excavated remains show that there was an arched entrance 2.7m (just under 9 feet) wide, with an oblong guardhouse on each side, projecting into the fort. This gatehouse was probably two or even three storeys high and about 5.5m (18 feet) in length. A nineteenth century excavation found two large bases of cylindrical columns of ‘whitish friable stone’ but it is not known exactly where these were.

Between Romney Marsh and the Pevensey Marshes, the followers of Haesta, the Haestingas, had settled and gave their name to the earliest beginnings of the town of Hastings and the area around it.

King Offa’s Charter

There are great gaps in Sussex history but we are told by Symeon of Durham, writing in the 11th century, that in 771 King Offa of Mercia “reduced the men of Hastings by force of arms”. The kingdom of Mercia covered the Midlands and at this period, included the control of both Wessex and Sussex.

The next year, it is said King Offa issued a Charter; unfortunately, only a 13th century copy survives and it has been stated that it is an “extremely corrupt text” (Brandon).

“Whereby, I, Offa, King of the English for the redemption of my soul and for the love of God assign in perpetual possession… a certain piece of land in Sussex to build there a minister church and enrich a public building which may be seen to serve the praise of God and the honour of the saints. That is to say 8 hides in the place which is called Bixlea “

Many of the Saxon charters are forgeries and enabled landholders to increase their lands by such forged ‘ancient’ claims. The charter has also been translated to mean the endowment of a pre-existing church.

The exact location of the land is difficult to pinpoint; tradition suggests it was in the old town because Saxon stone-work was found in St Peter’s Church during the restoration in the last century, together with the lid of a Saxon reliquary chest. However, the boundaries set out in the copy charter seem to be to the west of Little Common and this may be the land owned by the church in the 13th century.

Earl Godwin

Earl Godwin was a powerful Saxon earl, not particularly liked by King Edward the Confessor. Godwin used the south coast harbours including Hastings and Pevensey to support him in his power struggle with the king.

Assistance from the local people was demanded as Godwin was Earl of Kent and Wessex which included Sussex. This early alliance of south coast ports led to the formation of the Cinque Ports.

When St Peter’s church was altered in 1878 to Victorian taste, two important discoveries were made in the nave; firstly, it is recorded that ‘herring-bone’ stonework was discovered under the plaster suggesting Saxon origins, and, secondly, an intricately carved slab of stone was unearthed under the floor.

When St Peter’s church was altered in 1878 to Victorian taste, two important discoveries were made in the nave; firstly, it is recorded that ‘herring-bone’ stonework was discovered under the plaster suggesting Saxon origins, and, secondly, an intricately carved slab of stone was unearthed under the floor.

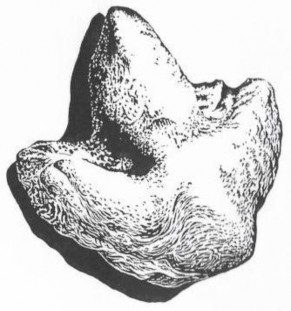

The stone slab (pictured) is known as the Bexhill Stone, and is a fine example of Saxon stonework. It was found under the floor of St. Peter’s Church when alterations to the church were carried out in 1878.

It is believed to be the lid of a box that contained holy relics and may date from the 8th to the early 10th century.

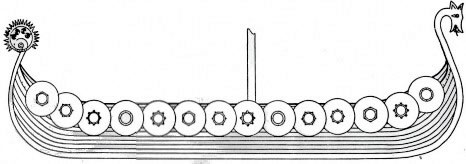

Viking Ship

Raids by Danish warriors affected the south coast including Sussex from 792-1011 .

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that this forced the Saxons to form some defences but it was found that giving them money and provisions was more effective in dispersing them.

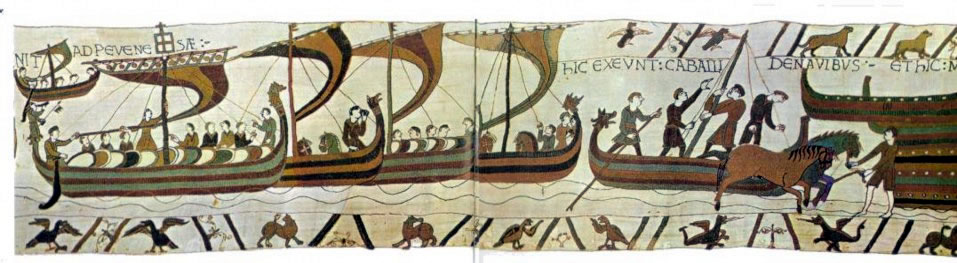

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry is of nearly contemporary date and states “Duke William on an immense fleet crosse the sea and arrived at Pevensey – here the horses are landed and here the soldiers hurried on towards Hastings to take food”. Duke William’s ship is shown with a lantern on top of the mast.

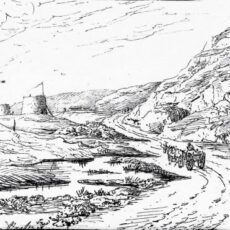

Duke William of Normandy, by tradition, landed at Pevensey with his invasion army on 28th September 1066. Current thinking suggests that the fleet landed along the stretch of coast from Pevensey to Hastings and possibly the Coombe Haven estuary. The quay at Pevensey was probably accessible by a tidal channel, navigable by the shallow draft boats of the time. How the invasion force grouped together is unclear but the settlements of the coastal area between Pevensey and Hastings suffered from raids for provisioning the army.

Duke William of Normandy, by tradition, landed at Pevensey with his invasion army on 28th September 1066. Current thinking suggests that the fleet landed along the stretch of coast from Pevensey to Hastings and possibly the Coombe Haven estuary. The quay at Pevensey was probably accessible by a tidal channel, navigable by the shallow draft boats of the time. How the invasion force grouped together is unclear but the settlements of the coastal area between Pevensey and Hastings suffered from raids for provisioning the army.

Bexhill suffered from the foraging and harrying of William’s troops.

The Domesday Book, of 1086, reports that “The value of the whole manor before 1066 [was] £20; later it was waste; now £18 10s.”

The term ‘waste’ indicates that the land was not cultivated and suggests that Bexhill was almost destroyed by the invading Normans.

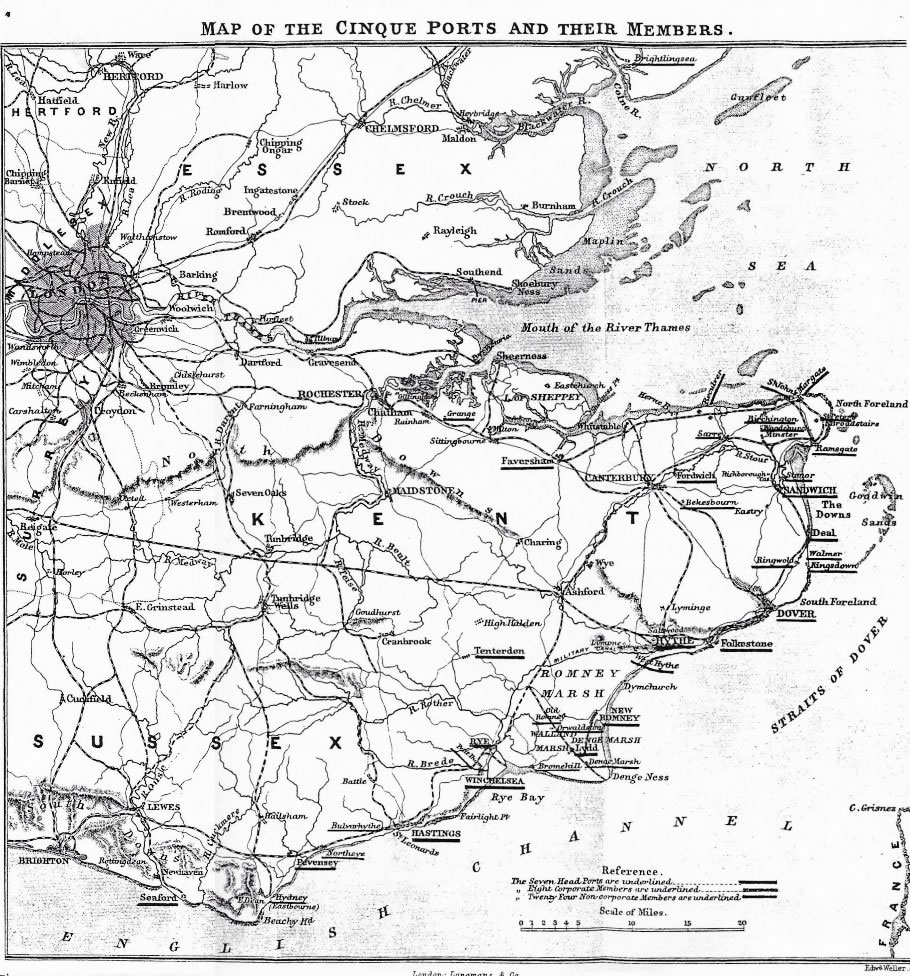

Cinque Ports

The importance of East Sussex and Kent ports was realised by Saxon kings who gave privileges to the ports to secure their loyalty. This grew into the Confederation of the Cinque Ports. The Confederation was formed of head ports, corporate limbs and non-corporate limbs. Northeye and Bulverhythe, west and east of Bexhill, were non-corporate members of the head port of Hastings.

Originally, the Cinque Ports (the first word is the French word for the number “5”, Cinque”, but this was Anglicised to ‘Sink’ many years ago) were a confederation of five harbours, Sandwich, Romney, Dover, Hythe, and Hastings plus the two Ancient Towns of Rye & Winchelsea. These were grouped together, for defence purposes, by Edward the Confessor.

Despite a decline in importance of many of the harbours, their privileges continued until the 19th century and their ceremonial aspects remain today.

Spanish Armada

In 1588 the Spanish Armada failed in its attempt to destroy the English fleet and land an invasion army on the south coast. The area had, however, been on a state of alert as the invasion was expected. Fire beacons were prepared and the Cinque Ports were called upon to supply ships and men. Locally, the Armada vessels would have been visible when becalmed off Fairlight on 27th and 28th July 1588.

Beacons

Fire beacons to warn of invasion were established in the 14th century and continued to be used intermittently until the early 19th century. Three sites have been identified in Bexhill, used at different times; Belle Hill, Cooden Mount and Whitehill.

It is possible that Barnhorn was also used. Early beacons would simply have been large bonfires on raised mounds. Later, purpose-built posts were erected on which tar barrels and metal baskets were placed.

The Napoleonic Threat

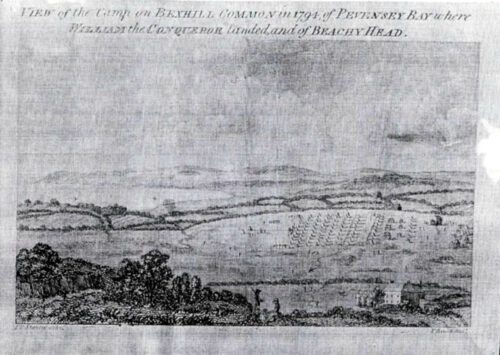

In May 1803 the British Government declared war in a resumption of hostilities with France. The Emperor of France, Napoleon I planned to invade England and while making preparations for this action, he sent an army to occupy Hanover, still ruled by King George III as Elector of Hanover. This resulted in some 12,000 troops of the Hanoverian army fleeing to England, 6,000 formed the King’s German Legion stationed at Bexhill.

In 1804, Napoleon Bonaparte massed the armies of revolutionary France at Boulogne, together with about 1,700 purposely built ‘bateaux plats’ – flat-bottomed barges capable of transporting troops, horses and artillery across the channel. He was annoyed that the Treaty of Amiens, signed on 25th March 1802, finally failed.

The British had not been happy with the Treaty as they would have had to have given up most of their islands in the West Indies, Egypt and Ceylon (now known as Sri Lanka), and Malta while it brought most of Europe under Napoleon’s control. The Treaty became, merely, a truce, a breathing space, a halt in the hostilities, which resumed in May 1803.

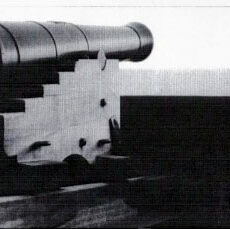

Britain, now, realised that it faced a serious threat of invasion so preparations for coastal defence in Sussex began in 1803. Coastal gun batteries were prepared between Eastbourne and Hastings, mainly covering low lying marshland areas. Plans were made to flood the Levels, in case of an enemy approaching the shore in force.

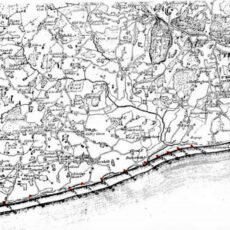

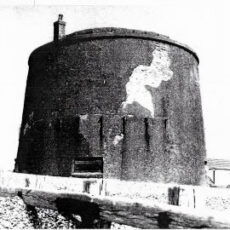

Martello Towers

Meanwhile a chain of defensive Martello Towers was built on the coastlines of Suffolk, Kent and Sussex. The towers are thought to be named after a tower defended by the French at Mortella Bay in Corsica. By 1810 seventy four towers had been built between Sandgate, Kent and Seaford in Sussex. Towers numbers 44 to 55 were in the area of Bexhill and are shown on the map below. All of those in Bexhill except no. 55 have suffered from erosion, neglect or demolition. Some of these towers are indicated, in red, on the map below.

Smuggling

The coast from Eastbourne to Hastings became notorious for smuggling, from the beginning of the 18th century to the mid-19th century. The open beaches and desolate marshlands of the Pevensey levels and Combe Haven were ideal for bringing ashore illicit cargoes to be taken to London, easily and quickly. The larger gangs of violent criminals used the area as well as smaller local gangs such as the ‘Little Common Gang’ of George Gillham. Both used local labourers to carry the goods while the gang members kept watch.

Smuggling declined towards the middle of the 19th century due to three factors; the reduction of duties on the commodities being smuggled; the formation of a sufficiently well-resourced and manned preventative service and the move politically to Free Trade.

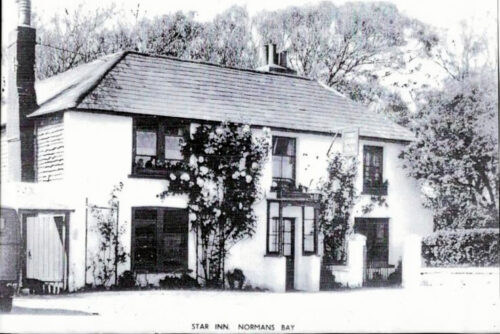

The Star Inn, Pevensey Sluice (now Normans Bay) is recorded in many reports as the scene of skirmishes between the local smugglers and the Preventative Services in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Smuggling still continues, even today, in illegal goods such as drugs and illegal immigrants.

Lords of the Manor

The bishops, first of Selsey then of Chichester, held the lordship of the Manor of Bexhill from 772 until 1561, except for a short time when Robert Count of Eu and Lord of Hastings Rape, held the manor after the Norman Conquest. Bishop Richard de Wych, a Sussex saint, is commemorated in the modern mural in St Peter’s church.

Bishop Ralph de Neville was Bishop of Chichester from 1224 to 1244. He served as Henry III’s chancellor. Bishop Adam de Moleyns was given permission by the king in 1448 to terrace the land around the Manor House at Bexhill. He was murdered by sailors in Portsmouth in 1450.

In 1570, Thomas Sackville was granted the Manor of Bexhill by Queen Elizabeth. Sackville was Lord Buckhurst and became 1st Earl of Dorset. He was the son of Sir Richard Sackville, a cousin of Anne Boleyn, who was the mother of Queen Elizabeth. He was held in high esteem — Lord High Treasurer, Lord High Steward, Chancellor of Oxford, and Lord Lieutenant of Sussex and was responsible for guarding the coastline against the Spanish Armada. In 1572, Mary Queen of Scots was told of her death sentence by him. He owned the Knole Estate, in Sevenoaks, in Kent.

The Sackville family were of Norman origin. The association of their family with Bexhill continued for more than 400 years but they, rarely, used the manor house, here, except as a hunting lodge.

Bexhill Manor

The first documentary reference to Bexhill is in a medieval copy of the Saxon charter of King Offa of Mercia dated AD772. This ordered a church to be built and this with the surrounding land was given to Bishop Oswald of Selsey. The bishops owned Bexhill manor up until the Norman invasion of 1066 when it was seized by William the Conqueror and given to the Count of Eu who also gained Hastings. Bexhill was given back to the bishops by the Count’s grandson John in 1148. The bishops stayed in the manor house at Bexhill when they were travelling around their diocese and was a useful place from which to keep an eye on their rivals the Abbots at Battle.

In 1570 Queen Elizabeth gave Bexhill Manor to Thomas Sackville whose descendants, the Dukes of Dorset held the land until the 19th century when the male line died out and the manor passed by marriage to the Earls De La Warr.

Lords and Ladies of the Manor of Bexhill

- 772 Bishop Oswald of Selsey – The Bishops moved to Chichester in 1075 1066 Robert Count of Eu

- 1148 Bishops of Chichester 1561 Bishopric vacant

- 1570 Thomas Sackville, Lord Buckhurst 1608 Henry Sackville

- 1608 Robert Sackville, 2nd Earl of Dorset 1609 Richard Sackville, 3rd Earl of Dorset 1624 Edward Sackville, 4th Earl of Dorset 1652 Richard Sackville, 5th Earl of Dorset 1677 Frances, Countess of Dorset

- 1688 Richard Sackville

- 1695 Charles Sackville, 6th Earl of Dorset 1706 Lionel Sackville, 7th Earl of Dorset

- 1765 George Sackville, ‘Lord George Germain’ 1785 John Frederick Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset

- 1799 Arabella Diana Sackville, Duchess Dowager of Dorset 1814 George John Frederick Sackville, 4th Duke of Dorset

- 1815 Charles Lord Viscount Whitworth & Arabella Diana, Duchess of Dorset 1825 Archer Windsor, Earl of Plymouth & Mary Countess of Plymouth

- 1829 Archer Windsor, 7th Earl of Plymouth 1833 Mary, Countess Dowager of Plymouth 1840 William Pitt Amherst, Earl Amherst 1863 Mary, Dowager Countess Amherst

- 1865 George John Sackville-West, 5th Earl De La Warr 1869 Elizabeth, Countess De La Warr

- 1870 Charles Richard Sackville-West, 6th Earl De La Warr 1873 Reginald Windsor Sackville, 7th Earl De La Warr

- 1895 Gilbert George Reginald Sackville, 8th Earl De La Warr 1916 Muriel Agnes, Countess De La Warr

- 1921 Herbrand Edward Dundonald Brassey Sackville, 9th Earl De La Warr 1976 William Herbrand Sackville, 10th Earl De La Warr

- 1988 William Sackville, 11th Earl De La Warr