A Bexhill Museum – World War 1 Project (Paul Wright)

Germany’s invasion of Belgium in August 1914 quickly led to a mass exodus of Belgians across the English Channel to Britain. It is estimated that about a quarter of million refugees had arrived in this country by the end of that year.

Although many made their way to London, a significant number of refugees went to Scotland, Wales and the West Country. Seaside resorts were popular because they had many empty hotel and bed-and-breakfast beds. For example, Blackpool housed around 8,000 Belgian refugees during the conflict.

The people of Bexhill reacted quickly to the plight of the Belgian refugees. In September 1914 Templemore, an old and empty convert at 5 Cranfield Road, was donated by the Sisters of Providence to house between 20 and 25 destitute refugees. The Bexhill Belgian Refugee Committee (BBRC) was soon established with 20 members and Mr William Reed-Lewis as Honorary Secretary. The Committee’s headquarters were established in Mr Reed-Lewis’ home at 24 Eversley Road. Mr Reed-Lewis was an American citizen who was already a prominent citizen of Bexhill as he had established in about 1912 the first public library in the town when about 25 books were made available in the porch of St Mary Magdalene’s Roman Catholic Church . He would become instrumental in drawing the plight of the refugees to the attention of the town as well as actively encouraging the necessary fund-raising activities. Hardly a week went by without a letter from him to the local newspapers asking for more help. He was ably assisted in this work by his wife Mary who spoke fluent French.

Above are four views of St Mary Magdalen’s Church.

Bexhill’s first Belgian refugees, four men, unfit for military service, and 10 women and children arrived by train from Folkestone on September 7th 1914. Their first night was spent in the Devonshire Hotel. Fund raising to support the refugees soon gathered pace with events such as concerts, bridge drives and afternoon teas as well as many collecting boxes around the town. In addition, clothes, furniture and surplus food were readily donated. Landlords offered empty houses and flats at no or minimal rent. The Corporation reduced the gas, electricity and water bills to houses accommodating refugees. The BBRC tried hard to ensure refugee families could remain together and relatively out of sight to maintain their dignity. There were never any public displays or parades of refugees to create sympathy. The BBRC provided for the needs of each family by knowing each individual’s requirements.

Felixstowe House was built in 1902 / 03 on the corner of Wickham Avenue and Woodville Road (where Woodville Court now stands). Initially it was a boarding house and in about 1915 the building became the Belgian Hostel run by Monsieur and Madame Leopold Sas. Although details are still unclear, about 35 Belgian refugees were accommodated there mainly professional and managerial men and their families. There is hardly any reference to this hostel or its occupants in the local papers throughout the whole of the war and there is an impression that these more upper-class refugees kept themselves apart from other refugees within the town.

During the war about 500 Belgian refugees were accommodated in Bexhill but there were only about 200 at any one time. Many were professional or middle class such as lawyers, magistrates, solicitors and two were the wives of Belgian cabinet members. These people brought and spent money in the town but there were many others who were poor and destitute and in need of plenty of support. It is unclear how many refugee children came to the town but photographs in the local papers suggest quite a few. They were sometimes taken for joy rides in large cars owned by wealthy Bexhillians. No accounts have been found regarding these children’s schooling. It has been suggested this was continued in private by, maybe, teachers amongst the adult refugees and maybe local private schools were also used by those who could afford them.

All the Belgian refugees were Roman Catholics and St Mary Magdalene’s Church played a very important part in giving them both practical and spiritual help during these difficult times. Father Kennedy was especially supportive of their needs. The times of mass were printed in the local papers in languages the refugees could understand.

In general, the refugees were well received and supported by the townsfolk. Fund raising was difficult but remained adequate. Language problems were a constant difficulty. A Reading Room was provided at the corner of Sea Road and Jameson Road where foreign language newspapers were available as well as books and games. Free admission was offered at the Colonnade, Kursaal and Bijou Cinema. But there are also first-hand reports of refugees waiting outside Down Elementary School (now King Offa Primary Academy) with their plates thrust through the railings hoping the Canadian troops stationed in the school would give them scraps of food. Christmas 1914 saw about 230 refugees in the town and after an appeal to the public large food hampers were distributed amongst the refugees. Toys were given to the children. A lengthy letter to a local newspaper from a Belgian refugee described the beauty of Bexhill especially the sea and the sunsets, the suffering of his country and his fellow countrymen. The writer expressed sincere thanks for the loving sympathy and true friendship of the people of Bexhill. The view of many in the local Belgian community was that it had been the best Christmas we have ever had in our lives. Up until July 1915 all funding to support the refugees had come from local sources. But additional funds were now being available by the London War Relief Fund on a pound for pound matched basis. The first Annual General Meeting of the BBRC held in September 1915 announced that approximately £3000 had been collected and spent supporting the refugees since their arrival.

Two major fund raising activities took place to support the refugees. The War Souvenirs Exhibition was held over five days in August 1915 at 14 St Leonards Road when 200 items of munitions, artefacts and photographs were displayed. Entrance was 6d for adults, 3d for children and £18 was raised. Over August Bank Holiday 1916 an auction was held of over 500 items including signed letters from Dickens, Kipling, Longfellow and Lewis Carroll. The three-day event started at the Colonnade and later moved to the Manor House. The local newspapers reported extensively both before and after the auction but without any photographs. A souvenir auction catalogue was also printed but none are known to remain. A total of £157 14s 6d was raised.

The War Charities Act became law in September 1916. This Act was the basis upon which all subsequent charities legislation has been based. Essentially the Act made it unlawful to make a public appeal for money or articles of kind unless the charity was registered and the charity approved the fund-raising activity. All suitable charities were invited to apply for registration. However, in September 1916 a letter from Mr Reed-Lewis in the local newspapers stated that following discussions within the BBRC they felt they could not comply with the requirements of this new Act. The Committee unanimously felt compliance with the Act would be detrimental to their work and as a consequence they were immediately disbanding the BBRC. They would not accept any further contributions from the public although all remaining funds would still be used for the support of refugees. Thereafter arrangements would be made with colleagues in London to care for the town’s refugees once local funds were exhausted. This sudden decision is difficult to understand. The membership of BBRC was still strong and fund raising was still adequate to meet the needs of local refugees. The BBRC claimed the new law would create more publicity for those receiving the Committee’s support, this it strongly opposed, as well as higher book-keeping costs. Yet by the end of 1916 at least 50 other charities within East Sussex alone had registered under the new Act so it remains difficult to understand the BBRC’s decision. Also, at the end of 1916 nobody then knew how long the war would last and what needs may be created by future refugees. Despite this sudden decision there were letters from refugees, town councillors, the London War Refugees Committee to the local newspapers thanking the BBRC for all its work. No critical voices were raised in public. So from September 1916 to the end of the War there was no co-ordinated support of the Belgian refugees in Bexhill.

By October 1916 there were 84 refugees in the town and the Belgian Hostel remained in use, especially by refugees with independent means, until early 1919. No births within the refugee community were recorded in the local newspapers but official birth records have not been reviewed. One marriage took place in September 1918 between two Belgians. Five deaths were recorded amongst the refugees, four in 1915 and one in 1919; all five were buried in Bexhill Cemetery. There were no headstones because of the costs involved but the plots used have been identified from Cemetery records.

Mr Reed-Lewis was awarded the OBE in June 1918 for his work with the Belgian refugees. He was also awarded the King Albert of the Belgians medal and in 1922 Pope Pius XI made him a Knight of St Gregory for his work in establishing the Catholic Library in Bexhill. Mrs Reed-Lewis and two other ladies of the BBRC were awarded the Queen Elizabeth of the Belgians medal for their work with the refugees.

Bexhill’s first war memorial, the Peace Memorial, at the corner of Sea Road and Magdalen Road was unveiled in November 1919. On the back of that memorial is an inscription dated 1920 dedicated to the Belgian refugees including the names of the five refugees who died. No details of an unveiling ceremony for the refugees’ memorial has yet been found.

Paul Wright

December 2013

Sources

There are a number of other potential sources: –

Magazine called “Ancestors” May 2005 p 45- 49 which gives general background information plus advice on further research.

Also “The Family and Local History Handbook”, edition 9, 2005, p 317 – 320 by Simon Fowler (Robert Blatchford Publishing). Again, happy to send you a copy if you cannot get hold of one yourself.

Both talk about the National Archives at Kew as a source of information in their War Refugees Committee minutes, papers and history cards.

Chronological Account

The Chronological account of the care given to Belgian refugees in Bexhill-on-Sea using information published in the Bexhill Observer and Bexhill Chronicle newspapers as well as other sources, 1914 – 1920

Additional notes

Appendices

1 Membership of the Bexhill Belgian Refugee Committee

2 Copy of Bexhill and the Belgians by William Reed-Lewis in the Bexhill Quarterly, November 1914, p11-19.

3 Report of Bexhill Belgian Refugee Committee Annual Meeting 1915.

4 Copy of How the Heart of Bountiful Bexhill Was Touched in the Bexhill Chronicle – Picture Chronicle, August 2nd 1916.

5 Copy of Bexhill Belgian Refugee Committee Receipts and Payments Account from September 1st 1914 to January 4th 1917.

6 Copy of The Story of Bexhill and the Belgians by Fred Wilson in the Bexhill Quarterly, March 1917, p1-12.

7 Copy of letter dated July 2nd 1917 written by Mr Reed-Lewis on behalf of the Belgian Sub-Committee for the County Relief Committee of East Sussex to the Hon Sec National War Museum Women’s Work Sub-Committee.

8 Copy of letter dated July 2nd 1917 written by Mr Reed-Lewis on behalf of the Bexhill Belgian Refugee Committee to the Hon Sec National War Museum Women’s Work Sub-Committee.

9 Known addresses of hostels and houses within Bexhill used by Belgian refugees

10 Inscription on the reverse of the Peace Memorial, St Mary Magdalene’s Church, Bexhill

11 Copies of the internment applications and death registrations of the five Belgian refugees recorded on the reverse of the Peace Memorial.

12 Extract from Haunted Places of Sussex by Judy Middleton, Countryside Books, 2005, page 44.

References

I would like to thank the following for their help and support in the preparation of this account. Julian Porter, Curator of Bexhill Museum; members of Local History Study Group and Jane Moseley, Bexhill Museum; staff at Bexhill Library; Rosemary Burt, Cemeteries Officer, Bexhill and Anita Hooper, St Mary Magdalene’s Parish Administrator, Bexhill.

Introduction

Following the German invasion of Belgium in August 1914, the start of the First World War saw an influx of refugees from Belgium to Britain. In September 1914 the British government offered “victims of war the hospitality of the British nation.” The British Government accepted the responsibility for the reception, maintenance and registration of Belgian refugees, while at the same time sought out assistance in housing the refugees with local authorities. The Belgian refugees, who totalled over a quarter of a million people, were the largest refugee movement in British history. Most of them had arrived by the end of 1914.

They entered mainly through the ports of Kent and the East coast and following the fall of Antwerp on October 7th 1914, around 11,000 disembarked at Folkestone on a single day. A further 26,000 arrived at Folkestone after the fall of Ostend later that month. By June 1915 it is estimated that 265,000 refugees had arrived in Britain from Belgian, of whom 40,000 were wounded soldiers and 15,000 were Russian Jews who had worked in Antwerp’s diamond industry.

Most people in Britain were sympathetic to the refugees and soon local relief charities and committees were established to look after their welfare and fund raising events were arranged. Accommodation was found, often in houses donated by well-wishers, the children enrolled in local schools, clothing and food provided and meaningful employment found for the adults who were unfit for active service. Nationally this relief work was co-ordinated by the War Refugees Committee.

Shops serving Belgian communities often sprang up where large numbers of refugees settled; the shop fronts sporting French or Flemish signs and advertisements. In Derby a local newspaper, Courier Belge, was printed for the Belgian community. In Birmingham a primary school was established which followed the Belgian syllabus and parents could chose whether their children were taught in French or Flemish. Refugees were spread fairly evenly throughout the country, including Scotland and Wales, although there were concentrations in London and seaside resorts, where there was plenty of out-of-season accommodation. For example, Blackpool housed about 8,000 Belgians.

Despite a general welcome during the early months, as the war progressed there often developed a general feeling amongst the local population that the Belgians were not contributing their fair share to the war effort, for example, fit young Belgians being reluctant to enlist in their army. However there were significant language and cultural barriers which were difficult for both sides to overcome as few British spoke Flemish or Walloon and vice versa .

One of the largest concentrations of Belgian refugees was in County Durham where a complete new village was constructed for them to live and work. It was situated at Birtley, a town between Chester-le-Street and Gateshead, and called Elisabethville, after Queen Elisabeth of the Belgians. The site was devoted to the production of munitions and over one and a half million shells were made there over the winter of 1915/16. This village was run according to Belgian law and protected by Belgian gendarmes, Flemish and Walloon was spoken and the currency was Belgian. After the Armistice most refugees returned home to Belgium with very few deciding to remain in Britain. In the early 1920s the Belgian government presented many memorials to local councils as a thank-you gesture. These took the form of plaques and monuments including the national “Monument of Belgium’s Gratitude for British Aid 1914-18” which can be found opposite Cleopatra’s Needle on theVictoria Embankment, London.

No information has been found regarding the education of the Belgian refugee children. Because of language difficulties for both the children and the local teachers it is unlikely that the refugee children attended any Bexhill schools. As middle and professional classes were well represented amongst the refugees it is possible that one or more of them were already trained teachers or were at least capable of continuing the children’s basic education in a language, and following a curriculum, with which the children were familiar. This schooling may have taken Aplace in the hall or rooms at St Mary Magdalene’s Church

Although a number of letters from prominent Belgian refugees during their time in Bexhill were printed in the local newspapers thanking the Committee and townsfolk for their care and support, no accounts have been found which describe any of the refugee’s personal experiences. Hence this account is based more or less on information and views expressed by British residents of Bexhill.

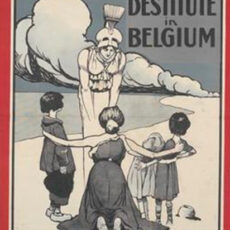

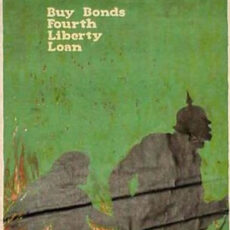

Below are a selection of posters shown during WW1 regarding the Belgian refugees.