Bexhill has an undeserved reputation as a sleepy seaside town where nothing much ever happens, even the most cursory scan though the town’s history shows that this was never the case but still the perception remains. Against this background certain key events blaze forth like beacons, powerful enough to cut through these misconceptions, but were these the exceptions that proved the rule or is it simply that the history of Bexhill is profoundly misunderstood?

-

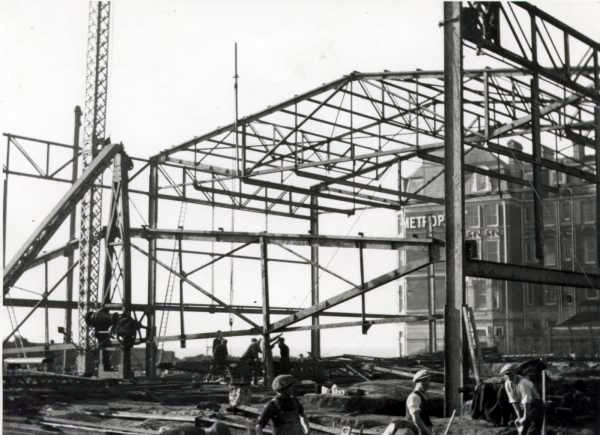

De La Warr Pavilion under construction 1935

The events in question are the rapid and dynamic development of the town at the end of the 19th century culminating in the incorporation of the borough in 1902, combined with radical departures from the norm such as being the first resort to allow mixed bathing in 1901, the 8th Earl’s innovation to host the country’s first automobile races in 1902 followed rapidly by the scandal of his divorce. Bexhill again proved its radical nature by constructing the De La Warr Pavilion in 1935, a municipal project advocated by the socialist 9th Earl De La Warr.

As with any community there were, and continue to be, divisions within the town and it would be difficult to prove whether these splits have acted as a catalyst and stimulated the town’s development or if they have held the town back by needless argument. The first main division was between parts of the town owned by Earl De La Warr’s estate and those which were not. This was most obvious on the sea front, the land south of the railway line to the west of sea road was given to John Webb, the building contractor who constructed most of the town in part payment for his work for the 7th Earl De La Warr, to the east of Sea Road was De La Warr Parade which was owned and managed by the Earl and his agents. Social divisions, in other words snobbery, was the problem here, trade and tradesmen were viewed as a necessary evil by the upper strata of society, useful, but never to be mixed with socially. The commercial infrastructure of the town was located in Webb’s territory which was known as the Egerton Park Estate and the high class housing, hotels and entertainment venues were mostly on De La Warr’s property.

The other division was usually typified as tradesmen versus residents, but this is an oversimplification and it does not correspond with the split between Webb’s estate and Earl De La Warr’s. The division is really between those dependent on tourism and those who were not, residents of independent means seemed to find visitors to the resort an intrusion but more importantly they were not prepared to pay for facilities to attract or for the use of visitors. At the heart of most, if not all, of the arguments within Bexhill were the rates, anything that would cost the ratepayers money was viewed with the deepest suspicion. Tourism of course was as important for the shopkeepers and publicans on Webb’s estate as it was for the hoteliers on De La Warr Parade they were mutually dependent on rich visitors coming to Bexhill and spending freely.

Entertainment on the seafront was based around two focal points, the Kursaal which was constructed in 1896 on De La Warr Parade and the Colonnade which was opened in 1911 on the Horn, a site which had been used for open air events and concerts since the resort was built. The cartoons of the period clearly show the social divisions between the two venues, the Kursaal for the upper middle classes and above and the Colonnade for the middle middle classes and below. This is the background against which the building of the De La Warr Pavilion must be viewed, it is usually considered the history of the Pavilion started in 1933 when the 9th Earl proposed and was nearly universally supported in his £50,000 scheme for a new entertainment pavilion but the demand for a new larger venue for Bexhill goes back much further than this. From 1907 various proposals were made for a ‘Winter Garden’ or some form of large enclosed entertainments pavilion, proposed sites included Egerton Park, the Kursaal and briefly in 1921 the roller-skating rink, which had opened in 1910, in Buckhurst Road was used as a winter garden. Development of Central Parade began in 1909 and culminated with the opening of the Colonnade in 1911, this was not free from controversy and a cartoon in the Christmas Edition of the Bexhill Observer of 1909 portrayed bands from the Kursaal and Colonnade trying to drown each other out and scaring away the town’s visitors in the process.

The Kursaal’s popularity began to decline after 1907 and the 8th Earl sold it to Mr Claude Johnson in 1908 and it was said that the Earl had lost some £30,000 over the building. The Kursaal was renamed the Pavilion during the first world war after an outcry in the tabloid press that Bexhill had an entertainment venue with a German name, it was substantially and unflatteringly modified in 1925 and it its last years gave Bexhill its first repertory company, Philip York’s Country Players which started in 1932. In 1912 and 1913 more cartoons appeared showing a winter garden on the seafront and the rivalry between the Kursaal and Colonnade which both wanted the be the site of the new pavilion.

In 1913 the Bexhill Corporation finally bought De La Warr Parade, the town first attempted to buy it in 1895 but would not meet the 8th Earl’s asking price and so he kept it, erected the De La Warr Gates enabling him to symbolically close off ‘his’ seafront and prompting him to become directly involved with the provision of entertainment on the estate. Shortly after the Corporation acquired the land they tore down the De La Warr Gates. The only portion of the seafront that was still in private hands was the Kursaal, an unsuccessful attempt was made to purchase it in 1927 but it was not until October 1935 that the Corporation was able to buy the Kursaal which it then demolished. The entire seafront was then in public ownership.

Section 180 of the Corporations Act of 1923 permitted councils greater expenditure of public buildings for entertainment and so paved the way for greater municipal development in Bexhill. The Corporation commissioned the consultants Adams, Thompson & Fry to produce a development plan for the town in 1926. A preliminary report was returned in 1927 and the final version was published in 1930 as The Bexhill Borough General Development Plan and advocated a radical redevelopment of the whole borough and included proposal for a ‘Music Pavilion and Enlarged Band Enclose’ on the Colonnade site. It is this scheme that seems to have tipped the balance in the favour of the Colonnade site rather than the Kursaal for the future construction of the De La Warr Pavilion. Needless to say most of the recommendations of the Plan were not implemented including the bold plan to redevelop Town Hall Square including a new railway station and a link joining the Crowhurst branch line onto the main line.

As mayor Cllr. A. Turner Laing outlined his plan for a new pavilion on the site of the coastguard station behind the Colonnade in January 1930. The plans were drawn up by the firm of Tubbs and Messer and the £50,000 scheme outlined an entertainments hall which included a museum, library and reading room. The long standing disagreement between those who wanted to promote Bexhill as a resort and those who wanted it to be entirely residential stopped the plan being implemented at this time.

In April 1933 the 9th Earl De La Warr as mayor of Bexhill proposed an new £50,000 plan for an entertainments hall on the coastguard site. Through shrewd politics and public consultation the project had overwhelming support, something that was almost unheard of in the town. The coastguard station closed in August 1930 making the land free for development. 9th Earl De La Warr commented:

“We all of us want to maintain the existing character of the town, but we believe that we can make more of our existing resources.”

The Earl was determined that the project should be funded by the town and not be a private development and said:

“My own view is if it is going to pay private enterprise it is going to pay the town.”

It was decided to ask the RIBA to hold a competition to design the new building and the choice of judge was made by president Sir Raymond Unwin. He selected Thomas S. Tait, who was respected by established architects but was known to be sympathetic towards the ideals of new ‘modernist’ architects.

The Bexhill Borough Council prepared a tight brief that indicated that a building in the modern style was wanted and that “heavy stonework is not desirable”. The competition was announced in The Architects Journal of 7 September 1933 and the closing date was on 4 December 1933, two hundred and thirty designs were submitted. The designs were displayed at the York Hall in London Road from 6 February to 13 February 1934 and the results of the competition were announced in The Architects Journal of 8 February 1934. So that the designs could be judged on their own merits the names of the architects were not revealed until after the judging had finished. The £150 first prize was won by Erich Mendelsohn and Serge Chermayeff, Tait commented that their design “indicated a thorough grasp of the nature of the problem, is direct and simple in planning, and shows a masterly handling of the architectural treatment.” Of the proposed entertainment hall he went on to say “This is the only scheme submitted showing a satisfactory treatment in this respect.” Mendelsohn and Chermayeff’s design was the clear winner and the correspondent for The Architects Journal commented “Mr Thomas S. Tait must have had little difficulty in choosing the winner.”

The only early objections to the project were from British fascists and one Bexhill resident who objected to ‘alien architects’ working in this country.

The submitted design was slightly different from what was built and the two minor criticisms that Tait made of the design were worked into the final version. The scheme was to have totally redeveloped the Colonnade site and to have linked this with the main building. In July 1935 the Council proposed to incorporate a swimming pool in the redeveloped Colonnade from which there also extended a small pier and diving board.

The cost of the project was initially estimated at £50,000, Mendelsohn and Chermayeff costed their initial design at £58,260 but at a meeting on 19 February 1934 it was decided to apply to the Ministry of Health for a loan of £80,000 to cover the project. To secure the loan a Public Inquiry was needed and held on two days from 5 April 1934. It was at this time the architect’s model was first displayed, which is still exhibited at Bexhill Museum. On 28 September 1934 permission was given for a loan of £70,000 to be repaid over 30 years and an addition £8,412 to be repaid over 15 years.

The spectre of ratepayers money being spent ignited opposition to the project and a residents association was formed to oppose the building of the Pavilion. Hostility over the nationality of the architects or the aesthetics of their design had to take second place to the real bugbear of the Council spending public money on a facility for the use of visitors. At a Council meeting on 28 October 1935 the decision to delay the £18,600 swimming pool at the Colonnade was made and on 19 November 1935 the plans for the £8,734 redesign of the Colonnade and the linking pergola were deferred. Neither scheme ever materialised. Early photographs of the Pavilion show that part of the pergola adjoining the main building was constructed but was subsequently removed. A huge statue by Frank Dobson was intended to stand on the south terrace of the Pavilion and although a maquette was exhibited the piece was never installed.

The building contract stated that the building work should be completed in fifty weeks and as much local labour as possible should be employed on the project. Construction began in January 1935. During March King George V and Queen Mary visited the Earl at Cooden Beach and expressed an interest in the model of the pavilion that they were shown and later went to see the building site.

A commemorative plaque was laid by the 9th Earl De La Warr on 6 May 1935, the Silver Jubilee Day of George V, and said:

“In doing so I mark a great day in the history of Bexhill, for which we have rightly chosen a great day in the history of our nation. How better could we dedicate ourselves today than by gathering round this new venture of ours, a venture which is going to lead to the growth, the prosperity and the greater culture of this, our town; a venture also which is part of a great national movement virtually to found a new industry – the industry of giving that relaxation, that pleasure, that culture, which hitherto the gloom and dreariness of British resorts has driven our fellow country men to seek in foreign lands. It is the expression of our determination to make a town, and therefore a body a citizens of which His Gracious Majesty King George V, even in this his jubilee, may be justly proud.”

The De La Warr Pavilion was opened by the Duke and Duchess of York on 12 December 1935, they were presented with a bouquet by Lady Kitty Sackville, daughter of the 9th Earl, who had only agreed to do so if she were accompanied by her friend Capt. Jim Stevens of the Bexhill Fire Brigade. The two had become close friends when the Brigade had named their fire engine after her.

The correspondent for the New Statesman of 1936 commented:

“You could not find a stronger argument in favour of town planning than Bexhill, which is not so much a town as a chaotic litter of hideous houses sprawling higgledy piggledy along a lovely coast. Lord De La Warr, whose ancestors were responsible for this muddle has now made an act of reparation. The most satisfactory example of modern architecture I have seen in this country…One has the impression of being on a great transatlantic liner. The Functionalists can complain that the staircase on the North side is mere ornament and its great glass bay looks only on buildings better not looked at – but it is a good ornament. The traditionalist on the other hand will complain that this is not so much a pleasure pavilion as a pleasure machine, ominously appropriate to the standard amusements of Mr Huxley’s Brave New World.”

Bernard Shaw wrote:

“Delighted to hear that Bexhill has emerged from barbarism at last, but I shall not give it a clean bill of health until all my plays are performed there once a year at least!”

Shaw attended a performance of his play The Millionairess at the De La Warr Pavilion in November 1936 and afterwards went behind stage to speak to the cast.

The Bexhill Corporation offered the 9th Earl the freedom of the Borough in June 1936 but he turned it down saying:

“I still feel it would be wiser for the matter to be deferred. It would naturally be pleasing to receive such an honour, feeling that it was with the approval of the Burgesses of Bexhill, but whilst so much controversy about the pavilion still exists, there would evidently be a certain number who would once again condemn the action of the council. I should naturally have been very proud and happy to receive such an honour, and you will easily understand that it is with grief and disappointment that I have come to this decision, but in the circumstances feel confident that I am adopting the only course possible.”

The building suffered bomb damage during the Second World War and a Dilapidation Report was written by Johannes Schreiner in 1944. Schreiner had been Mendelsohn’s assistant during the original work on the Pavilion and he presented a plan for building a dance hall on the east end of the building and an extension on the south side from the theatre, neither of which were implemented.

Various unflattering modifications were made to the building in the 1950s and there was even an attempt to hide the building under ivy in the 1970s. Restoration work during the 1990s has made the building structurally sound and improved the appearance of the inside of the Pavilion but the building’s future role within the town now appears to be uncertain. The De La Warr Pavilion is not Bexhill’s only claim to fame but it is certainly the one that is best known, the national and international significance of the building cannot be doubted. It was controversial when it was first built and the controversy has never diminished. The town showed itself to be progressive and forward-thinking in 1935 and has never quite recovered from the shock, it is still startling to see such a radically different architectural design within the town.

Bexhill Museum Association May 2000

The events in question are the rapid and dynamic development of the town at the end of the 19th century culminating in the incorporation of the borough in 1902, combined with radical departures from the norm such as being the first resort to allow mixed bathing in 1901, the 8th Earl’s innovation to host the country’s first automobile races in 1902 followed rapidly by the scandal of his divorce. Bexhill again proved its radical nature by constructing the De La Warr Pavilion in 1935, a municipal project advocated by the socialist 9th Earl De La Warr.

As with any community there were, and continue to be, divisions within the town and it would be difficult to prove whether these splits have acted as a catalyst and stimulated the town’s development or if they have held the town back by needless argument. The first main division was between parts of the town owned by Earl De La Warr’s estate and those which were not. This was most obvious on the sea front, the land south of the railway line to the west of sea road was given to John Webb, the building contractor who constructed most of the town in part payment for his work for the 7th Earl De La Warr, to the east of Sea Road was De La Warr Parade which was owned and managed by the Earl and his agents. Social divisions, in other words snobbery, was the problem here, trade and tradesmen were viewed as a necessary evil by the upper strata of society, useful, but never to be mixed with socially. The commercial infrastructure of the town was located in Webb’s territory which was known as the Egerton Park Estate and the high class housing, hotels and entertainment venues were mostly on De La Warr’s property.

The other division was usually typified as tradesmen versus residents, but this is an oversimplification and it does not correspond with the split between Webb’s estate and Earl De La Warr’s. The division is really between those dependent on tourism and those who were not, residents of independent means seemed to find visitors to the resort an intrusion but more importantly they were not prepared to pay for facilities to attract or for the use of visitors. At the heart of most, if not all, of the arguments within Bexhill were the rates, anything that would cost the ratepayers money was viewed with the deepest suspicion. Tourism of course was as important for the shopkeepers and publicans on Webb’s estate as it was for the hoteliers on De La Warr Parade they were mutually dependent on rich visitors coming to Bexhill and spending freely.

Entertainment on the seafront was based around two focal points, the Kursaal which was constructed in 1896 on De La Warr Parade and the Colonnade which was opened in 1911 on the Horn, a site which had been used for open air events and concerts since the resort was built. The cartoons of the period clearly show the social divisions between the two venues, the Kursaal for the upper middle classes and above and the Colonnade for the middle middle classes and below. This is the background against which the building of the De La Warr Pavilion must be viewed, it is usually considered the history of the Pavilion started in 1933 when the 9th Earl proposed and was nearly universally supported in his £50,000 scheme for a new entertainment pavilion but the demand for a new larger venue for Bexhill goes back much further than this. From 1907 various proposals were made for a ‘Winter Garden’ or some form of large enclosed entertainments pavilion, proposed sites included Egerton Park, the Kursaal and briefly in 1921 the roller-skating rink, which had opened in 1910, in Buckhurst Road was used as a winter garden. Development of Central Parade began in 1909 and culminated with the opening of the Colonnade in 1911, this was not free from controversy and a cartoon in the Christmas Edition of the Bexhill Observer of 1909 portrayed bands from the Kursaal and Colonnade trying to drown each other out and scaring away the town’s visitors in the process.

The Kursaal’s popularity began to decline after 1907 and the 8th Earl sold it to Mr Claude Johnson in 1908 and it was said that the Earl had lost some £30,000 over the building. The Kursaal was renamed the Pavilion during the first world war after an outcry in the tabloid press that Bexhill had an entertainment venue with a German name, it was substantially and unflatteringly modified in 1925 and it its last years gave Bexhill its first repertory company, Philip York’s Country Players which started in 1932. In 1912 and 1913 more cartoons appeared showing a winter garden on the seafront and the rivalry between the Kursaal and Colonnade which both wanted the be the site of the new pavilion.

In 1913 the Bexhill Corporation finally bought De La Warr Parade, the town first attempted to buy it in 1895 but would not meet the 8th Earl’s asking price and so he kept it, erected the De La Warr Gates enabling him to symbolically close off ‘his’ seafront and prompting him to become directly involved with the provision of entertainment on the estate. Shortly after the Corporation acquired the land they tore down the De La Warr Gates. The only portion of the seafront that was still in private hands was the Kursaal, an unsuccessful attempt was made to purchase it in 1927 but it was not until October 1935 that the Corporation was able to buy the Kursaal which it then demolished. The entire seafront was then in public ownership.

Section 180 of the Corporations Act of 1923 permitted councils greater expenditure of public buildings for entertainment and so paved the way for greater municipal development in Bexhill. The Corporation commissioned the consultants Adams, Thompson & Fry to produce a development plan for the town in 1926. A preliminary report was returned in 1927 and the final version was published in 1930 as The Bexhill Borough General Development Plan and advocated a radical redevelopment of the whole borough and included proposal for a ‘Music Pavilion and Enlarged Band Enclose’ on the Colonnade site. It is this scheme that seems to have tipped the balance in the favour of the Colonnade site rather than the Kursaal for the future construction of the De La Warr Pavilion. Needless to say most of the recommendations of the Plan were not implemented including the bold plan to redevelop Town Hall Square including a new railway station and a link joining the Crowhurst branch line onto the main line.

As mayor Cllr. A. Turner Laing outlined his plan for a new pavilion on the site of the coastguard station behind the Colonnade in January 1930. The plans were drawn up by the firm of Tubbs and Messer and the £50,000 scheme outlined an entertainments hall which included a museum, library and reading room. The long standing disagreement between those who wanted to promote Bexhill as a resort and those who wanted it to be entirely residential stopped the plan being implemented at this time.

In April 1933 the 9th Earl De La Warr as mayor of Bexhill proposed an new £50,000 plan for an entertainments hall on the coastguard site. Through shrewd politics and public consultation the project had overwhelming support, something that was almost unheard of in the town. The coastguard station closed in August 1930 making the land free for development. 9th Earl De La Warr commented:

“We all of us want to maintain the existing character of the town, but we believe that we can make more of our existing resources.”

The Earl was determined that the project should be funded by the town and not be a private development and said:

“My own view is if it is going to pay private enterprise it is going to pay the town.”

It was decided to ask the RIBA to hold a competition to design the new building and the choice of judge was made by president Sir Raymond Unwin. He selected Thomas S. Tait, who was respected by established architects but was known to be sympathetic towards the ideals of new ‘modernist’ architects.

The Bexhill Borough Council prepared a tight brief that indicated that a building in the modern style was wanted and that “heavy stonework is not desirable”. The competition was announced in The Architects Journal of 7 September 1933 and the closing date was on 4 December 1933, two hundred and thirty designs were submitted. The designs were displayed at the York Hall in London Road from 6 February to 13 February 1934 and the results of the competition were announced in The Architects Journal of 8 February 1934. So that the designs could be judged on their own merits the names of the architects were not revealed until after the judging had finished. The £150 first prize was won by Erich Mendelsohn and Serge Chermayeff, Tait commented that their design “indicated a thorough grasp of the nature of the problem, is direct and simple in planning, and shows a masterly handling of the architectural treatment.” Of the proposed entertainment hall he went on to say “This is the only scheme submitted showing a satisfactory treatment in this respect.” Mendelsohn and Chermayeff’s design was the clear winner and the correspondent for The Architects Journal commented “Mr Thomas S. Tait must have had little difficulty in choosing the winner.”

The only early objections to the project were from British fascists and one Bexhill resident who objected to ‘alien architects’ working in this country.

The submitted design was slightly different from what was built and the two minor criticisms that Tait made of the design were worked into the final version. The scheme was to have totally redeveloped the Colonnade site and to have linked this with the main building. In July 1935 the Council proposed to incorporate a swimming pool in the redeveloped Colonnade from which there also extended a small pier and diving board.

The cost of the project was initially estimated at £50,000, Mendelsohn and Chermayeff costed their initial design at £58,260 but at a meeting on 19 February 1934 it was decided to apply to the Ministry of Health for a loan of £80,000 to cover the project. To secure the loan a Public Inquiry was needed and held on two days from 5 April 1934. It was at this time the architect’s model was first displayed, which is still exhibited at Bexhill Museum. On 28 September 1934 permission was given for a loan of £70,000 to be repaid over 30 years and an addition £8,412 to be repaid over 15 years.

The spectre of ratepayers money being spent ignited opposition to the project and a residents association was formed to oppose the building of the Pavilion. Hostility over the nationality of the architects or the aesthetics of their design had to take second place to the real bugbear of the Council spending public money on a facility for the use of visitors. At a Council meeting on 28 October 1935 the decision to delay the £18,600 swimming pool at the Colonnade was made and on 19 November 1935 the plans for the £8,734 redesign of the Colonnade and the linking pergola were deferred. Neither scheme ever materialised. Early photographs of the Pavilion show that part of the pergola adjoining the main building was constructed but was subsequently removed. A huge statue by Frank Dobson was intended to stand on the south terrace of the Pavilion and although a maquette was exhibited the piece was never installed.

The building contract stated that the building work should be completed in fifty weeks and as much local labour as possible should be employed on the project. Construction began in January 1935. During March King George V and Queen Mary visited the Earl at Cooden Beach and expressed an interest in the model of the pavilion that they were shown and later went to see the building site. A commemorative plaque was laid by the 9th Earl De La Warr on 6 May 1935, the Silver Jubilee Day of George V, and said:

“In doing so I mark a great day in the history of Bexhill, for which we have rightly chosen a great day in the history of our nation. How better could we dedicate ourselves today than by gathering round this new venture of ours, a venture which is going to lead to the growth, the prosperity and the greater culture of this, our town; a venture also which is part of a great national movement virtually to found a new industry – the industry of giving that relaxation, that pleasure, that culture, which hitherto the gloom and dreariness of British resorts has driven our fellow country men to seek in foreign lands. It is the expression of our determination to make a town, and therefore a body a citizens of which His Gracious Majesty King George V, even in this his jubilee, may be justly proud.”

The De La Warr Pavilion was opened by the Duke and Duchess of York on 12 December 1935, they were presented with a bouquet by Lady Kitty Sackville, daughter of the 9th Earl, who had only agreed to do so if she were accompanied by her friend Capt. Jim Stevens of the Bexhill Fire Brigade. The two had become close friends when the Brigade had named their fire engine after her.

The correspondent for the New Statesman of 1936 commented:

“You could not find a stronger argument in favour of town planning than Bexhill, which is not so much a town as a chaotic litter of hideous houses sprawling higgledy piggledy along a lovely coast. Lord De La Warr, whose ancestors were responsible for this muddle has now made an act of reparation. The most satisfactory example of modern architecture I have seen in this country…One has the impression of being on a great transatlantic liner. The Functionalists can complain that the staircase on the North side is mere ornament and its great glass bay looks only on buildings better not looked at – but it is a good ornament. The traditionalist on the other hand will complain that this is not so much a pleasure pavilion as a pleasure machine, ominously appropriate to the standard amusements of Mr Huxley’s Brave New World.”

Bernard Shaw wrote:

“Delighted to hear that Bexhill has emerged from barbarism at last, but I shall not give it a clean bill of health until all my plays are performed there once a year at least!”

Shaw attended a performance of his play The Millionairess at the De La Warr Pavilion in November 1936 and afterwards went behind stage to speak to the cast.

The Bexhill Corporation offered the 9th Earl the freedom of the Borough in June 1936 but he turned it down saying:

“I still feel it would be wiser for the matter to be deferred. It would naturally be pleasing to receive such an honour, feeling that it was with the approval of the Burgesses of Bexhill, but whilst so much controversy about the pavilion still exists, there would evidently be a certain number who would once again condemn the action of the council. I should naturally have been very proud and happy to receive such an honour, and you will easily understand that it is with grief and disappointment that I have come to this decision, but in the circumstances feel confident that I am adopting the only course possible.”

The building suffered bomb damage during the Second World War and a Dilapidation Report was written by Johannes Schreiner in 1944. Schreiner had been Mendelsohn’s assistant during the original work on the Pavilion and he presented a plan for building a dance hall on the east end of the building and an extension on the south side from the theatre, neither of which were implemented.

Various unflattering modifications were made to the building in the 1950s and there was even an attempt to hide the building under ivy in the 1970s. Restoration work during the 1990s has made the building structurally sound and improved the appearance of the inside of the Pavilion but the building’s future role within the town now appears to be uncertain. The De La Warr Pavilion is not Bexhill’s only claim to fame but it is certainly the one that is best known, the national and international significance of the building cannot be doubted. It was controversial when it was first built and the controversy has never diminished. The town showed itself to be progressive and forward-thinking in 1935 and has never quite recovered from the shock, it is still startling to see such a radically different architectural design within the town.

Bexhill Museum AssociationMay 2000

Contemporary Comments:

Mr Tait

“Thorough grasp of the nature of the problem, was direct and simple in planning, and showed a masterly handling of the architectural treatment.”

Daily Express 1934

“perfect British sea front”

“the seaside town of tomorrow is going to be built at Bexhill-on-Sea today”

9th Earl De La Warr May 1936 on laying the foundation stone of the Pavilion

“In doing so I mark a great day in the history of Bexhill, for which we have rightly chosen a great day in the history of our nation. How better could we dedicate ourselves today than by gathering round this new venture of ours, a venture which is going to lead to the growth, the prosperity and the greater culture of this, our town; a venture also which is part of a great national movement virtually to found a new industry – the industry of giving that relaxation, that pleasure, that culture, which hitherto the gloom and dreariness of British resorts has driven our fellow country men to seek in foreign lands. It is the expression of our determination to make a town, and therefore a body a citizens of which His Gracious Majesty King George V, even in this his jubilee, may be justly proud.”

New Statesman 1936

“You could not find a stronger argument in favour of town planning than Bexhill, which is not so much a town as a chaotic litter of hideous houses sprawling higgledy piggledy along a lovely coast. Lord De La Warr, whose ancestors were responsible for this muddle has now made an act of reparation. The most satisfactory example of modern architecture I have seen in this country…One has the impression of being on a great transatlantic liner. The Functionalists can complain that the staircase on the North side is mere ornament and its great glass bay looks only on buildings better not looked at – but it is a good ornament. The traditionalist on the other hand will complain that this is not so much a pleasure pavilion as a pleasure machine, ominously appropriate to the standard amusements of Mr Huxley’s Brave New World.”

9th Earl De La Warr, writing re. Freedom of the borough

“I still feel it would be wiser for the matter to be deferred. It would naturally be pleasing to receive such an honour, feeling that it was with the approval of the Burgesses of Bexhill, but whilst so much controversy about the pavilion still exists, there would evidently be a certain number who would once again condemn the action of the council. I should naturally have been very proud and happy to receive such an honour, and you will easily understand that it is with grief and disappointment that I have come to this decision, but in the circumstances feel confident that I am adopting the only course possible.”

9th Earl De La Warr,

“We all of us want to maintain the existing character of the town, but we believe that we can make more of our existing resources.”

“My own view is if it is going to pay private enterprise it is going to pay the town.”

Sir Charles Reilly, Professor of Architecture at Liverpool University 1935

“There is the Bexhill concert hall, clean, elegant and efficient, without a break in walls or ceilings for piers or beams, a revelation from another planet in the rococo redness of that terrible town.”

Building Magazine

” One of the most significant buildings to be erected in this country in recent years”

“It performed the usual stunt of digging out a few of the oldest inhabitants and asking them for their prehistoric opinions. The old inhabitants were flattered and overwhelmed and no doubt their old heads wagged with joy when they saw their obsolete opinions given such prominence. We would as soon look to a teetotaller for a golden opinion of a drunken or to Mussolini for praise of Haile Selassi.”

Hannen Swaffer 1937, Daily Herald

” If only people knew, I am going round the English sea-coast, choosing a nice town of which I can become Mayor. So far I have chosen Bexhill.”

“The truth was that after the war Bexhill was ‘dying’. Its visitors declined in numbers. People were flocking abroad. There seemed to be little future for the town. Fortunately its ground landlord, Lord De La Warr, brought up in the Socialist faith – he ‘went over’ of course with Ramsay – was a man of foresight and courage.”

“Even today some Bexhill people think the pavilion either an eyesore or a white elephant. It costs the town, you see, an eightpenny rate.”

“Councilllor Corbett, standing for the first time last November, personnally canvassed every house in the Tory ward he was fighting. ‘Are you a Conservative?’ asked one woman. No, he replied. I am a Socialist. ‘Then I am afraid I can’t vote for you’ she said. ‘If you were a national Socialist it would not be so bad. Why the Socialists gave us that dreadful pavilion. It was Earl De La Warr’. He is a Nationalist Specialist explained Corbett walking away.”

“The De La Warr Pavilion stands on the sea coast, a challenge, not only to other towns, but a challenge to its own.”

Alderman Bending 1932, described the Council thus:

“Like a number of doctors standing around the patient’s bed arguing as to the best means of curing him, but, failing to agree as to a remedy, allowing the patient to continue to suffer and even grow worse.”

RIBA asked to nominate as a judge for the competition

“A man who was in touch with modern ideas of architectural development, in order that the younger generation of architects would feel that their plans would receive sympathetic and understanding treatment at his hands.”

The choice was that of the President of RIBA Sir Raymond Unwin and he chose Thomas S. Tait.