The history of Conscientious Objectors and Pacifists in the First World War is often overlooked and in an attempt to erase this chapter from history the vast majority of tribunal records were deliberately destroyed in the 1920s. Despite the negative and insulting wartime propaganda aimed at Conscientious Objectors only 2% of appeals made to the Military Tribunals for exemption from fighting were made on conscientious grounds. The more common reasons included domestic, financial and medical.

The Government had also realised that not every man could enlist as this would cause problems at home. As early as October 1914 the large number of volunteers enlisting were causing serious labour shortages. The Government identified reserved occupations such as railway workers, miners and farmers who could be given complete exemption, although this was not always automatic. There were also other occupations such as dentists, chemists, doctors, grocers, bakers, and coal merchants, who could be given exemption if their enlistment would cause severe hardship to the public. Civil servants from certain government departments were also given exemption as they were considered to be doing “war work”. In order to demonstrate they were not “shirkers” these men were given badges to wear and so these professions became known as “badged occupations”.

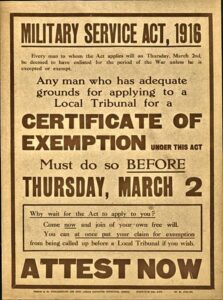

In 1916 the Military Service Act introduced Conscription for the first time. The “Conscience Clause” was added to the Act because of pressure from various groups who had seen the inevitability of conscription and because of their religious beliefs or a strong conviction against taking a human life, considered that they should be exempt or take a non-combatant role. It is from this clause that the term “Conscientious Objector” was coined.

There were four stated grounds for exemption:

1. If it was beneficial to national interests that the man should be engaged in other work, or, if he was being educated or trained for any other work that he should continue.

2. If serious hardship would follow owing to the man’s exceptional financial or business obligations or serious family problems.

3. Ill health, physical disability or medical unfitness.

4. Conscientious objection to the undertaking of combatant service. The “Conscientious Clause”

A system of military tribunals was established to hear the cases of men who applied for exemption on one of these grounds. The tribunals could award temporary exemption to allow a man to get his affairs in order, order them into non-combatant roles, award full exemption, imprison them, or refuse exemption completely and force the man to enlist. If the men disagreed with the local tribunals ruling they could appeal to the County and Central tribunals. In Bexhill the local tribunals were reported in depth in the local newspapers. Some men appeared again and again requesting extensions to their exemption or fighting for the exemption of their staff. One Bexhillian, Sidney Wickens, even managed to avoid enlistment all together! However, there are also examples at the Bexhill Tribunals of men being sent to war when they were blind in one eye, and others who were almost completely deaf.

Bexhill’s Conscientious Objectors

From the Bexhill Observer it is possible to identify at least 14 Conscientious Objectors connected to the town.

They were:

- Private Paul Alexander

- Private John Bastin

- Private Alfred Horace Bignall

- Private William Bristow

- Private James William Burt

- Bombardier Arthur Percy Coleman

- Earl De La Warr, Edward Herbrand Sackville

- Private Anthony Thomas Gammon

- Private George Norman

- Henry James Sargent, (no rank)

- Private Berti Truluck

- Private Frederick Truluck

- Private John Truluck

- Sidney Harold Wickens (no rank)

Twelve of them were forced into either non-combatant roles or into the armed services. Out of the two remaining, one successfully avoided enlistment entirely and continued to run his business while the other was imprisoned in dreadful conditions and kept in solitary confinement.

Treatment

Treatment

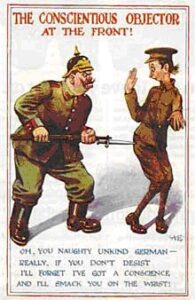

Conscientious Objectors were often treated terribly by the public with women being encouraged to avoid all contact with men who would not fight and for employers to refuse to employ them. Their masculinity was attacked and they were often portrayed as effeminate cowards and many received a white feather from the Order of the White Feather for cowardice. For some men who refused to accept the ruling of a tribunal they could also find themselves court-martialed and sentenced to prison for varying lengths of time. The punishment could include hard labour and solitary confinement sometimes for months or even years. Bexhill Museum’s longest serving Curator Henry Sargent was a Conscientious Objector who was imprisoned for many years during the War.

The Reluctant Tommy

In 2010 the memoir The Reluctant Tommy; Ronald Skirth’s Extraordinary Memoir of the First World War was published by Macmillan. Ronald Skirth grew up in Bexhill and had been a student at St. Barnabas School. During the First World War he saw action at the Battle of Messines and the Battle of Passchendaele. In The Reluctant Tommy, Skirth, who served in the Royal Garrison Artillery, claimed that during the First World War he became a Pacifist and a Conscientious Objector after witnessing the death of friends at the Front and after finding the dead body of a German soldier who he realised may have been killed by a shell he targeted. Around 1917 following treatment for shell shock Skirth decided he would do anything within his power to avoid the loss of more human lives, including purposefully missing his target when firing the guns.

In 1999 Skirth’s daughter donated his memoirs to the Imperial War Museum. However following the book’s release in 2010, many leading historians began to criticise his recollections as many of his descriptions did not match official war records. He also accused fellow soldier, Bombardier Bromley, of accidently killing five fellow soldiers and covering it up. A descendent of Bromley’s was outraged by these claims and produced convincing evidence that the event had never happened. At first the Imperial War Museum stated they would remove the memoir from their collection, but when they found out the descendent was planning to publicise her findings, they simply added her research to the memoir. Skirth’s daughter later admitted that many of his stories had been embellished for her enjoyment.

Following this controversy, Macmillan added a new section to the introduction of all future copies of The Reluctant Tommy explaining the difference between a memoir and a factual autobiography.