Kate Marsden was born in Edmonton, North London, on 13th May 1859; she was the 8th and youngest child of a London solicitor, Joseph Daniel Marsden, born in London in 1814, and his wife, Sophia Matilda, née Wellsted, born 1822 in Marylebone, Middlesex. Kate was one of only three who survived death from tuberculosis. Alter her father died, Kate trained as a nurse at Tottenham Hospital and, in 1877, she volunteered as a nurse for the Russo-Turkish war in Bulgaria. It was in Bulgaria that Kate encountered her first victim of leprosy and she became determined to find a way to help its sufferers. Her plan was to set up a charity to relieve the condition of Iepers in India so she sought, and got, the support of both Queen Victoria of England and the Tsarina of Russia, Maria Fedorovna.

Kate Marsden was born in Edmonton, North London, on 13th May 1859; she was the 8th and youngest child of a London solicitor, Joseph Daniel Marsden, born in London in 1814, and his wife, Sophia Matilda, née Wellsted, born 1822 in Marylebone, Middlesex. Kate was one of only three who survived death from tuberculosis. Alter her father died, Kate trained as a nurse at Tottenham Hospital and, in 1877, she volunteered as a nurse for the Russo-Turkish war in Bulgaria. It was in Bulgaria that Kate encountered her first victim of leprosy and she became determined to find a way to help its sufferers. Her plan was to set up a charity to relieve the condition of Iepers in India so she sought, and got, the support of both Queen Victoria of England and the Tsarina of Russia, Maria Fedorovna.

At this stage, she had no inkling of any journey to Siberia; her focus was, solely, on India. She set off for Palestine, Egypt, Cyprus and Constantinople to study how leprosy was treated in different colonies. It was in Constantinople that she met an English doctor who told her of a rare and unnamed herb, known only to the Yakut people in that faraway permafrost region. Inspired by its potential, she changed her plans and rushed back to the royal capital of St Petersburg to set up an expedition into Siberia to find that herb. To that end she, once again, secured the support of both Queen Victoria, the Empress of the sub-continent, and Alexandra, the Princess of Wales and sister of the Tsarina of Russia.

By the time of her trip, she had already made her mark, and had won the hearts of Russians as a battle-hardened nurse caring for the wounded during the war between Russia and Turkey, in 1878. There are accounts of her, then aged 19, stalking the battlefield at night, bringing relief to soldiers felled during the day’s fighting. It was at this time that she had her first contact with lepers, and it was to their cause that she devoted her lifers work. Seeking further patronage, and never fearful of aiming high to secure her ends, she travelled to St Petersburg and sought the assistance of the Russian Empress, with Alexandra’s introduction.

In November 1890 she not only convinced the Empress to fund a trip to distant Yakutia to find this herb and use it to cure lepers around the world, she, also, secured from the Tsarina orders to local governors across eastern Russia that they should give Marsden all possible assistance in the name of Her Majesty. Now in her early 30s, she knew from the start that the herb was a closely guarded secret but she hoped that the audacity of her mission would persuade locals to give up their knowledge. “Could they be persuaded to reveal all they knew to a woman who came to them for the sake of humanity, and on behalf of Christ?”, she wondered.

She set out for Russia in February 1891 and, in an era of extraordinary adventurers, hers was especially noteworthy in this era both because she was a woman travelling alone, and due to the sheer scale of her undertaking, to reach one of the remotest areas of Yakutia, in Siberia, in search of the elusive herbal cure for leprosy.

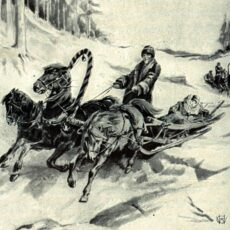

She did not find the mythical herb or a cure for leprosy but she helped to establish a new hospital for lepers in Siberia, having drawn attention to their plight. In 1893 Kate Marsden published a book, “On sledge and Horseback to outcast Siberian lepers” and was nominated as a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, becoming one of their first female members. She has a large diamond named after her and is still remembered in Siberia, where a large memorial statue was crated at Sosnovka village in 2014.

On 26th August 2014, the ceremony was reported in the on-line newspaper “Siberian Times” and shown below, in the picture gallery, are the images, with captions, as they appeared in that newspaper.

They are reproduced here with the kind permission of Svetlana Skarbo, editor of the “Siberian Times” and Anna Liesowska author of the original article. Anna has, also, given permission for her story of the ceremony, and Kate’s time in Siberia, to be reproduced by the Museum, and you can read that HERE.

The “Siberian Times” can be read on-line at http://siberiantimes.com and it is well worth a visit to see a world that the west is, generally, not aware of.

Some years after her return from Siberia, Kate Marsden went to live in the USA, returning to England in about 1902. In 1911, in the census of that year, Kate was living in Shanklin, Chine Side, Isle of Wight, sharing the occupation (as ‘Head’) with the daughters of a clergyman: two sisters Emily Lloyd Norris and Alice Margaret Norris.

When they took up occupation isn’t known but Kate Marsden and the Norris sisters lived in various places (St Leonards on Sea in 1910, the Isle of Wight in 1911) before settling in Bexhill on Sea in about 1912.

The idea of a Town Museum emerged in, about, 1912 and, while other people claimed much of the credit, Marsden was, really, at the forefront from the start, using methods at which she was adept because of her experiences in the past.. She organised public meetings with all interested parties and with as many of the great and the good that lived in Bexhill.

This time she sought the support, not of Queens and Empresses but an admiral and an archdeacon. She, as she had done before, organised considerable newspaper coverage though, this time, it was the Bexhill Observer and not the international press. She set up an exhibition of objects suitable for the Museum and sought other, suitable, items for the Museum from prominent companies such as Bryant & May (match manufacturers), Fry’s (Chocolate and cocoa) and Colman’s (mustard), as well as from the Imperial Institute in London.

She donated her collection of tropical shells, most probably acquired in Honolulu and/or New Zealand, and the Museum’s most important objects – the Egyptology collection, donated by her friend, Dr Walter Amsden, medical officer to the British School in Egypt – Dr Amsden was a local physician who had worked with archaeologists such as William Flinders Petrie and Rex Engclbach.

Progress was made until the Mayor of Bexhill contacted the committee and claimed that Marsden had been involved in a controversy concerning her finances and her sexuality. Marsden was obliged to resign: the museum still opened on 22nd May, 1914, but without her.

Kate Marsden and the Reverend J. C. Thompson FGS had planned to open the Museum together – she gave it her shell collection and encouraged

The Rev. Thompson served as voluntary Curator until 1924. The local corporation provided a small grant and also gave the museum the use of a building in Egerton Park known as the Egerton Park Shelter Hall. This glass roofed hall had been built in 1903.

The controversy surrounding Kate Marsden was never resolved and she lived out ha days suffering from dropsy and senile decay. After she died, the museum refused a portrait that was offered to the museum that she had helped to create. Her Russian watch, medals, whistle and a brooch given to her by Queen Victoria were sent to the Royal Geographical Society.